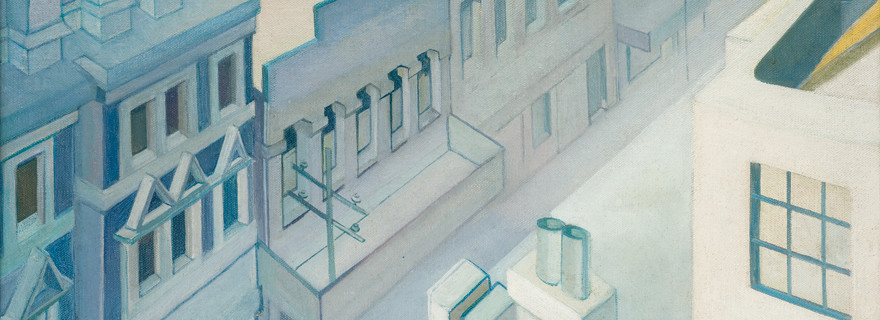

Alfred Charles Barker Government Buildings, Christchurch N.Z., from N.E. Nov. 29, 1861 1861. Glass negative. Canterbury Museum 1944.78.121

Laying out Foundations

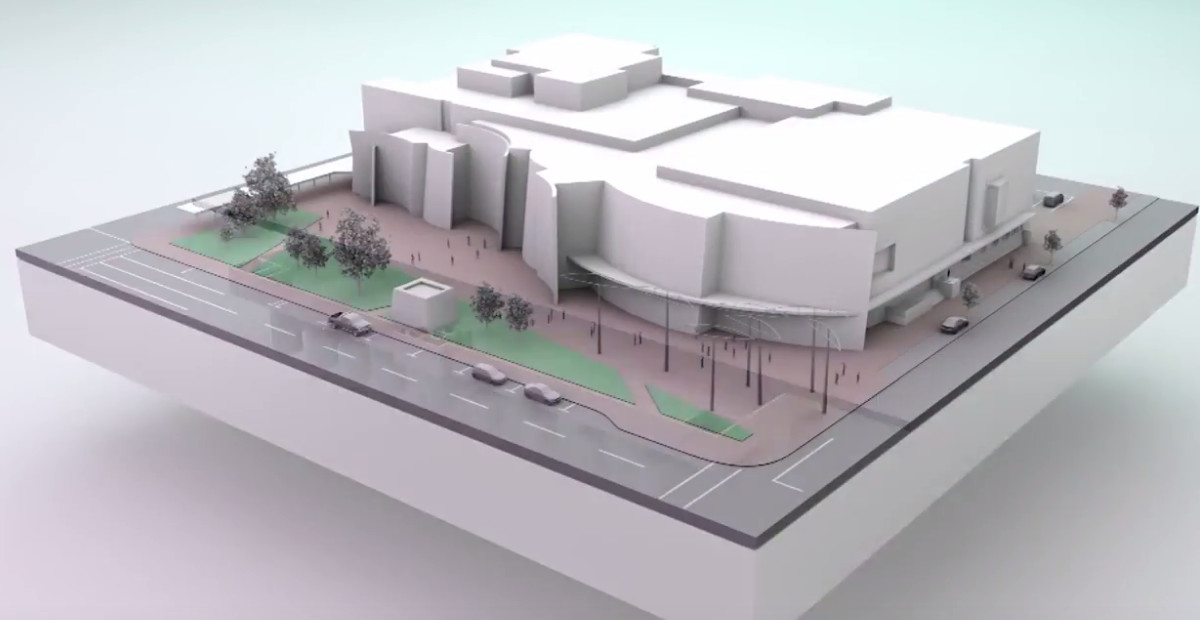

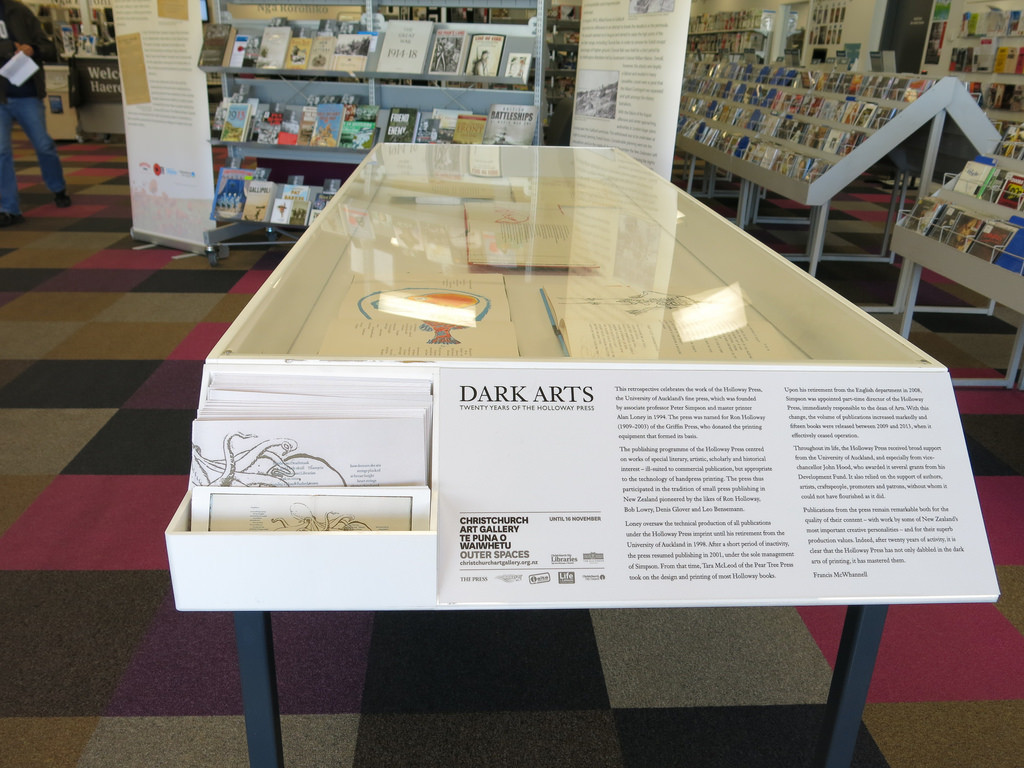

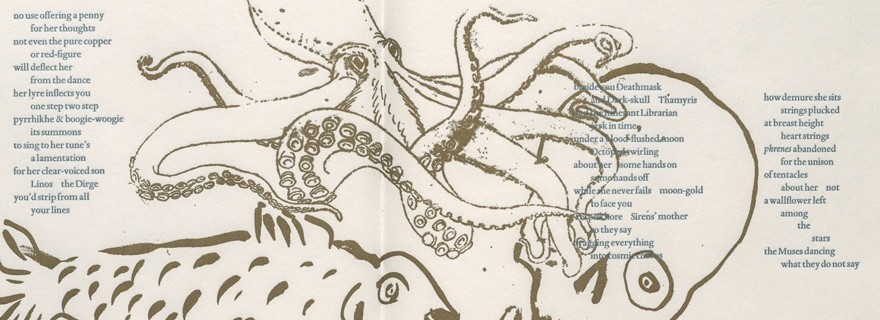

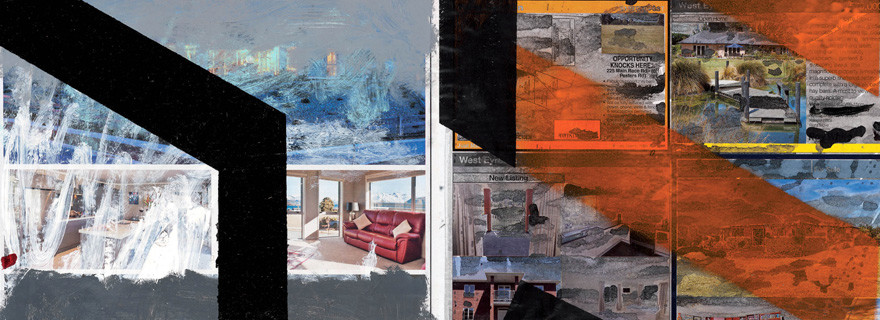

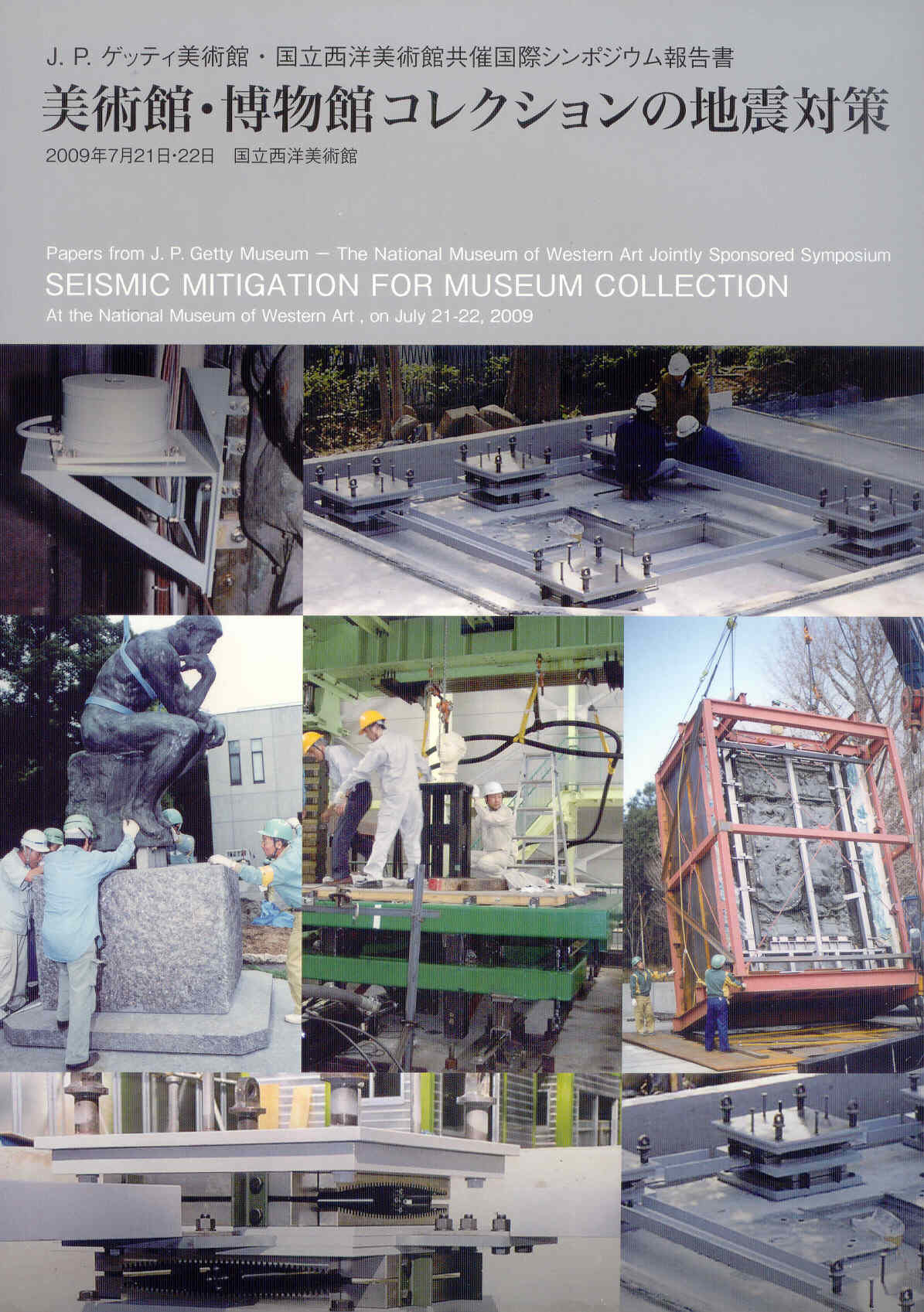

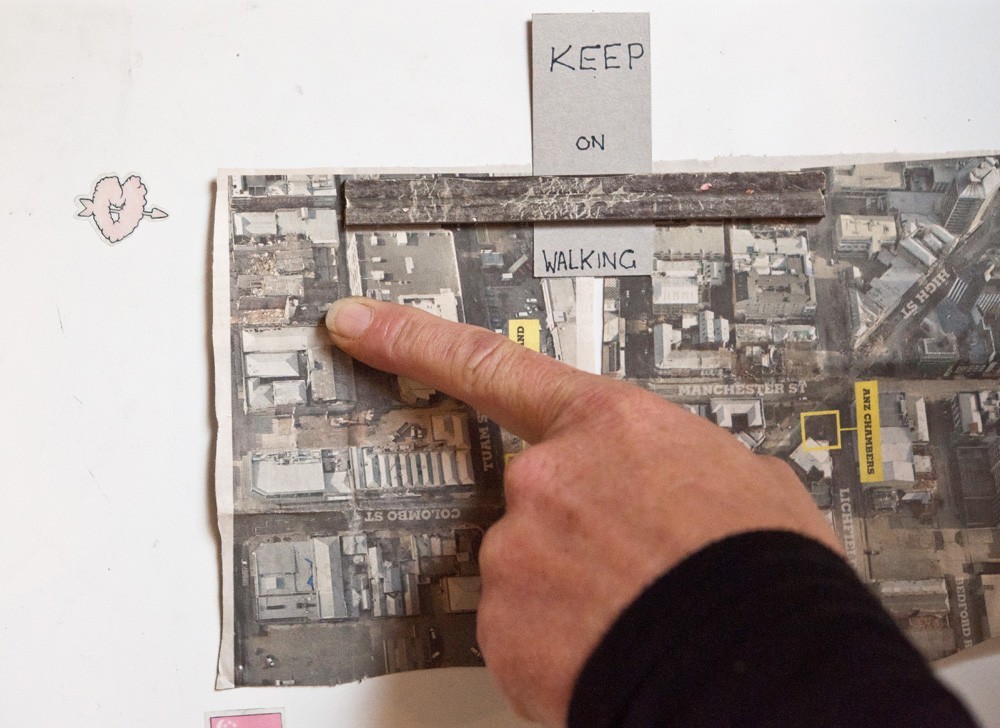

Looking broadly at the topic of local architectural heritage, Reconstruction: conversations on a city had been scheduled to open at the Gallery but will now instead show on outdoor exhibition panels along Worcester Boulevard from 23 June. Supplementing works from the collection with digital images from other collections, curator Ken Hall brings together an arresting art historical tour of the city and its environs.

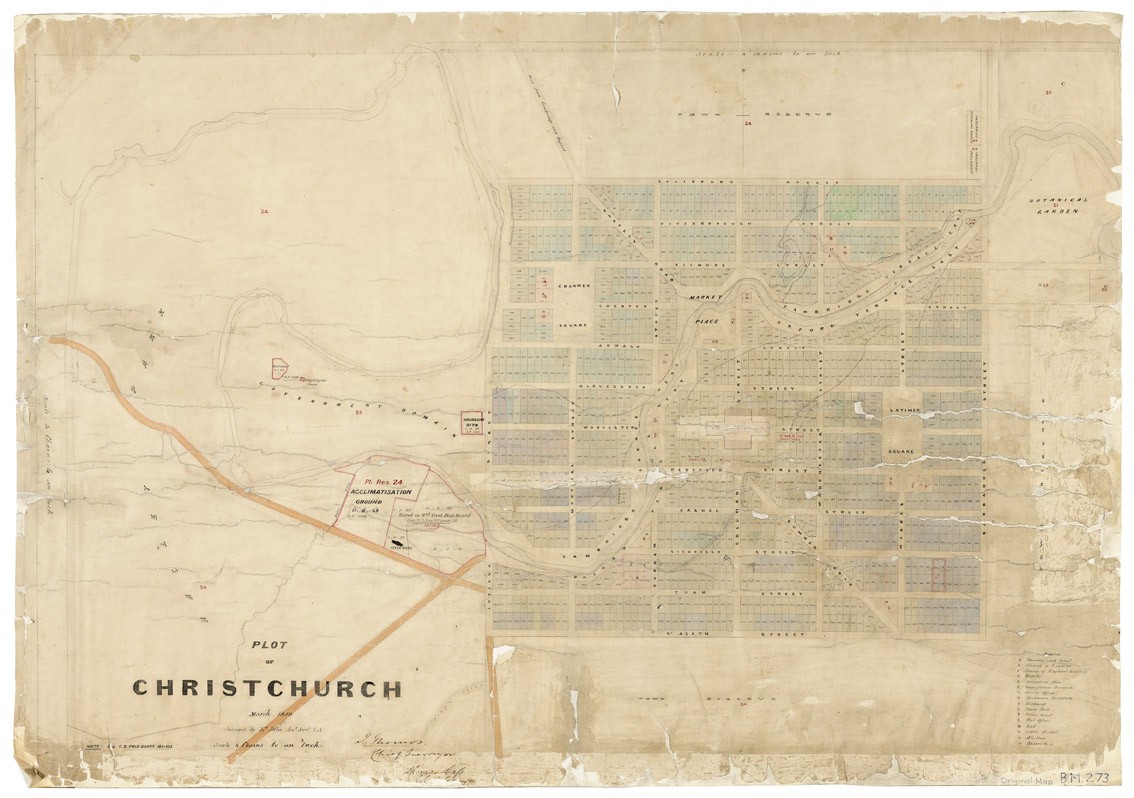

Edward Jollie Black map 273, Plot of Christchurch, March 1850, sheet 1 1850. Ink and watercolour. Archives New Zealand Christchurch Office, archives reference: CAYN 23142 CH1031/179 item 273/1

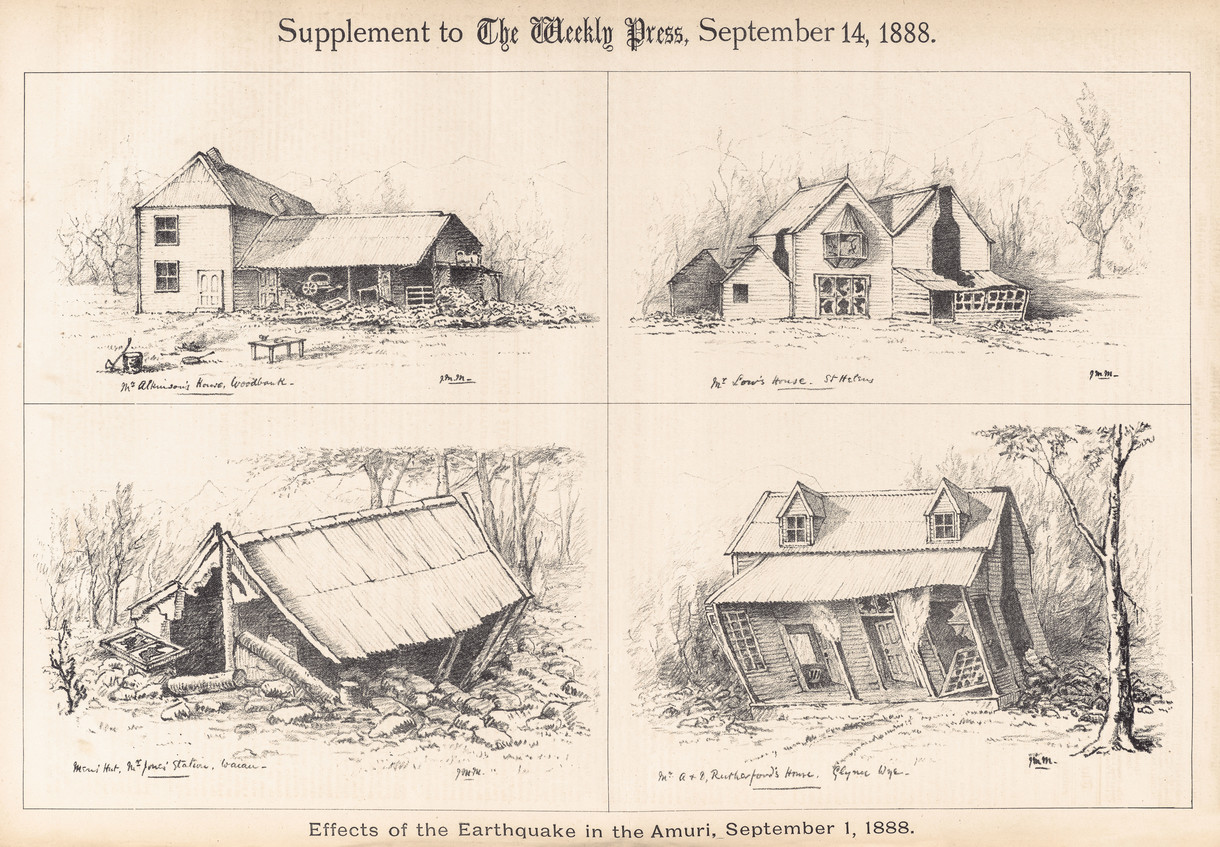

It feels somewhat overwhelming to be bringing this particular visual history into the midst of the heritage disaster that is our present Christchurch. But the images selected for Reconstruction seem to matter, and they leave a strong imprint. The diverse gathering of digitised drawings, paintings, plans, photographs and prints offers a telling account of how this place came to be; tracking the story through stills from a historical documentary spanning 164 years provides a clear sense of narrative being played out. It's a movie with transfixing moments and some unpleasant twists – you already know it has a bad ending, but can only hope that when the sequel has been written, the story will not have completely fallen apart. Meanwhile, the eradication of surviving heritage structure in this city continues on an unimaginable scale. At present the exhibition seems more a memorial to the city's rapidly fading architectural past than a vessel that might yet uphold or safeguard heritage values. The images may be all that we have left.

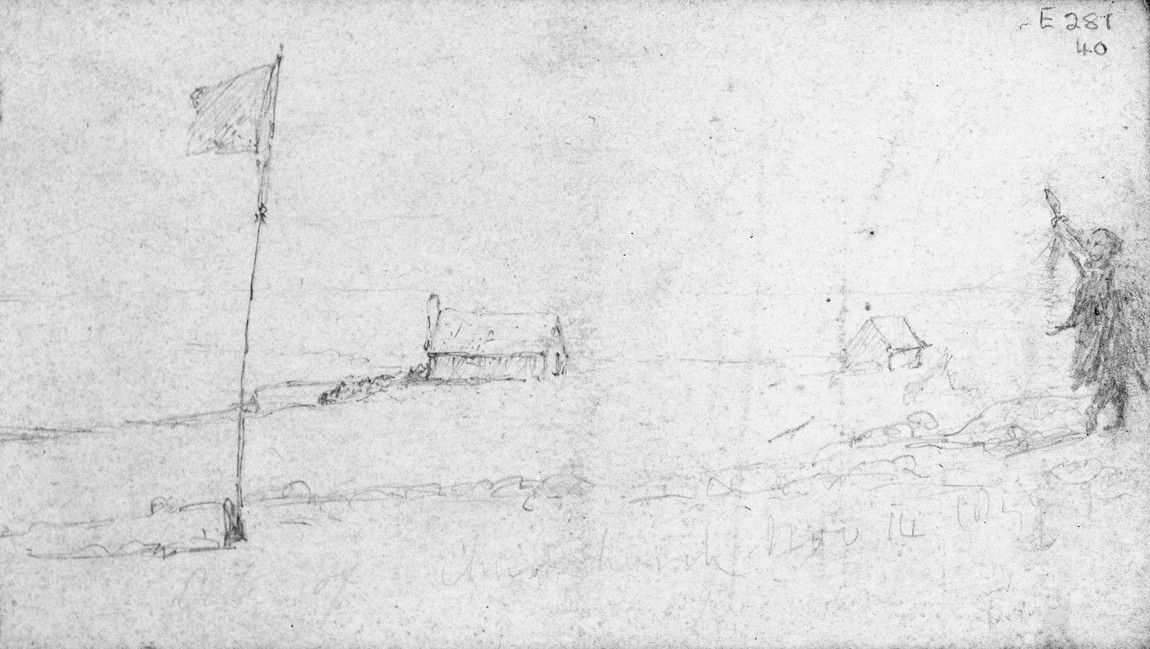

Walter Baldock Durrant Mantell City of Christchurch Nov 14 1849 1849. Pencil. National Library of New Zealand, Alexander Turnbull Library, E-281-q-040

Reconstruction makes no claim to being comprehensive, but aims to provide clarity around the circumstances into which Christchurch was born. Enter a faded pencil drawing – the first known image created within the city's planned boundaries – made thirteen months before the arrival of the first Canterbury Association settler ships.1 It's a disconcerting start. Walter Mantell's City of Christchurch Nov 14 1849 shows two wooden surveyor's huts, one with a chimney, on a site that would become known as The Bricks, a landing place for boats on the Avon River by the corner of what is now Salisbury and Barbadoes streets. To their left, a slender flagpole holds an open flag; to the right a dignified Māori figure in a rain cape displays a taiaha, decided strut and (suggested by rapid pencil strokes) generous, outstretched hand. Mantell is no artist and the drawing – like his job title, 'Commissioner for the Extinguishment of Native Titles' – does his reputation no particular favours. But if firsts matter then the sketch is an important record of a moment in time.2 By March 1850, just four months later, the now well-known 'Black Map of Christchurch' would have the planned city within the Four Avenues neatly laid out.3

Examples of local Māori architecture are seen in the work of a small number of explorer/surveyor/ settler artists, including William Fox, Richard Oliver, Frederick Weld and Charles Haubroe. Providing an invaluable record of Ngāi Tahu settlements beyond the immediate Christchurch vicinity are watercolours painted between 1848 and 1855 by Fox at Te Rakawakaputa (near present-day Kaiapoi), Oliver at Purau, Weld at Rāpaki and Haubroe at Kaiapoi. As depictions of a people and way of life soon to be overwhelmed by the expansionist ways of the British Empire, these paintings may at the same time be interpreted as representing a period of new beginnings for Ngāi Tahu. Following a period of devastating intertribal warfare, peace, faith and reconciliation have come. At this moment the people are rebuilding, in a sense starting again (some of the buildings depicted will have been new); imagining perhaps that the newcomers will be accommodated into their changing world.

![William Fox Rakawakaputa, P. Cooper Plains. 1848 [Te Rakawakaputa, Kaiapoi Wataputa 20 Decr 1848; Wataputa on Canterbury Plain. Jan 1849, from Fox sketchbook] 1848. Watercolour. Hocken Collections Uare Taoka O Hakena University of Otago](/media/cache/3c/28/3c287555bd6be15d6a8bc46a934423e3.jpg)

William Fox Rakawakaputa, P. Cooper Plains. 1848 [Te Rakawakaputa, Kaiapoi Wataputa 20 Decr 1848; Wataputa on Canterbury Plain. Jan 1849, from Fox sketchbook] 1848. Watercolour. Hocken Collections Uare Taoka O Hakena University of Otago

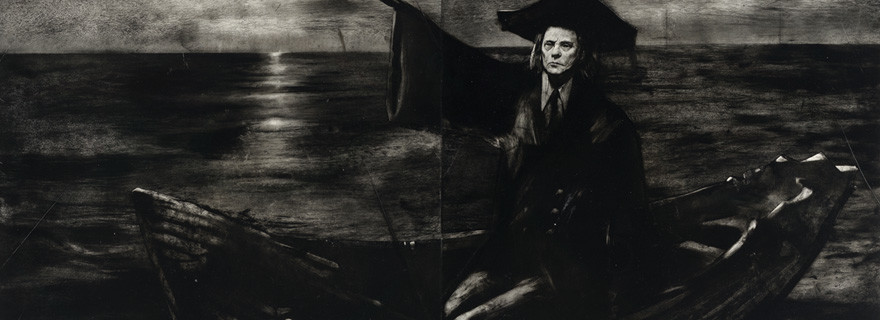

Those who wield pencil and brush, however, are part of the strengthening colonial tide, the scale of which is unforeseen. Soon to be made effectively landless, Ngāi Tahu will wait a long time before those in power make honourable amends. John Robert Godley's Canterbury Settlement – an idealistic new society filled with towering spires, far from his beloved Christ Church College in Oxford, England – could have almost been anywhere, and at one point was being considered for the Wairarapa. From the end of 1850 onwards, as a good number of watercolour sketches show, the Canterbury settlers and their simple structures – tents, makeshift huts and prefabs – begin to spill out of Lyttelton, up and across the land. In the vast scrubland plain, partly swamp, the Christchurch grid will be slowly filled, every single building to begin with raised purely in relation to practical concerns. It will not be long before talent and greater ambitions are ready to perform. The city's founding and transitional stages will be exquisitely chronicled by Dr Alfred Charles Barker (ship's surgeon from the Charlotte Jane, the first Canterbury Association ship to reach Lyttelton) in pencil and watercolour, then with his ever-present camera. Barker's shipmate (and photography tutor), the architect Benjamin Woolfield Mountfort, will make the greatest initial impact on the architectural fabric of the new city. His Canterbury Provincial Council Buildings emerging from the swamp in this early period must be admired as a remarkable feat. Owing a debt of inspiration to Charles Barry's new Houses of Parliament at Westminster, Mountfort's scaled-down labyrinth as it grows from the laying of a foundation stone in 1858 is like a breathing thing; distant beams and struts in Barker's photographs expanding like ribcages into glorious life. The showcase within this set of buildings – and Mountfort's acknowledged greatest achievement among many – is his magnificent Stone Council Chamber, completed in 1865.

Certain excerpts from this early period bring it unexpectedly close. This from a Lyttelton Times writer in January 1858:

We have a chance now of making a healthy and pleasant town of Christchurch; and we ought not to commit in a new country the old-world mistake of leaving no lungs for a town which will soon become populous. ... We are living in a climate more like that of France than that of England; – the French are wiser than we are in providing glimpses of vegetation in the centre of towns as an antidote against the effects of a hot summer sun upon weary and feverish populations. Let us look a little to the future.4

Or perhaps this from Alfred Barker (writing to his brother Matthias in England) on 8 June 1869:

We had a most tremendous & peculiar earthquake here on Saturday last – I was lying in bed, ill, at 8 a.m. when I heard a sudden warning noise – not the deep distant rumbling usually accompanying an earthquake – the house was violently shaken – to the sore destruction of chimneys crockery & chimney ornaments – & in a few seconds all was quiet – the chimneys were wrenched round – & I have since had to take them down. In the town a good deal of mischief was done – but no lives lost – The majority of people agree that the undulatory motion came from N.E. to S.W. or vice versa – it has been succeeded by a vibratory & apparently rotator motion – but the oddest part is it was entirely confined to Christchurch & its vicinity – the shock seemed to come from directly beneath us – but strange to say it did not affect the artesian wells at all. This is the first earthquake which did not give me the sensation of sea sickness.5

(And now I am distracted, wondering how many quakes Barker can have experienced during his nineteen years in the region to be surprised – this time – not to be feeling seasick.)

The West Coast Times added more details about the impact of Christchurch's quake:

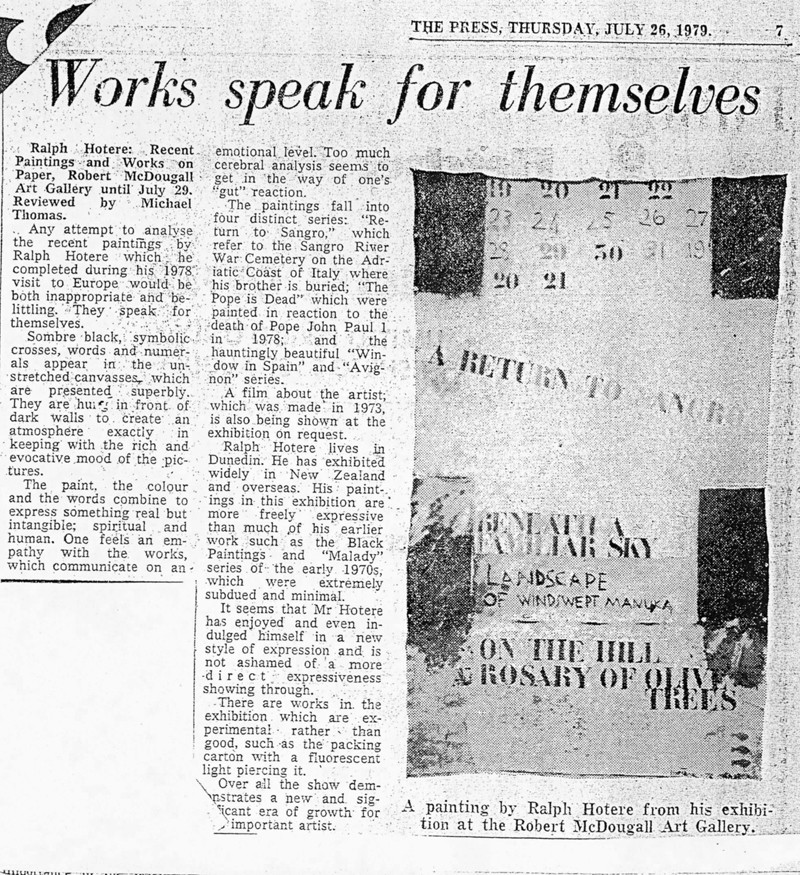

[It] inflicted considerable damage. The Government buildings, the Bank of New South Wales, the Town Hall, and other stone buildings, are greatly cracked and injured. A large number of chimneys are thrown down, and others will have to be taken down. It has been the severest shock ever felt here.6

We kept building the city and the quakes we forgot. Beautiful, elaborate productions arose, inspired by London, Oxford, Venice or Rome. Gothic spires appeared everywhere: schools, libraries and university; courthouses and cricket pavilions; museum, railway station and asylum; numerous churches; the tallest, long-awaited, on ChristChurch Cathedral. Sturdy temples dedicated to sacred or secular pursuits embraced the excitement of Gothic revival, Venetian Gothic, neo-classical, Queen Anne or Georgian revival. The proliferation of architecture – serious architecture – meant that Mountfort, provincial architect from 1864, found ready competition from trained and talented others, including Samuel C. Farr, Thomas Cane, W.B. Armson, J.C. Maddison, J.J. Collins, R.D. Harman and Samuel Hurst Seager.7 Appropriations and adaptations from Roman avenues and villas, the Colosseum or Bath Guildhall showed up in Cathedral Square or on Colombo, Manchester, Worcester, High, Cashel, Hereford and Lichfield streets. Dreams embodying cultural accomplishment, past and present, solidified and defined the city. Stone, brick and concrete reinforced the impression of permanence and stability, while timber retreated into the role of hidden structural support.

When Canterbury's founder J.R. Godley left New Zealand in 1852, the town of Christchurch was still just a few wooden huts scattered across swampy scrubland, yet his farewell speech displayed his pride in what the settlement had already become:

When I first adopted and made my own the idea of this colony, it pictured itself to my mind in the colours of a Utopia. Now that I have been a practical coloniser, and have seen how these things are managed in fact, I often smile when I think of the ideal Canterbury of which our imagination dreamed. Yet I have seen nothing in the dream to regret or to be ashamed of, and I am quite sure that without the enthusiasm, the poetry, the unreality (if you will), with which our scheme was overlaid, it would never have been accomplished.8

He concluded with the thought that 'The Canterbury Association has done its work and passed away', maintaining that they had done, 'a great and heroic work; they have raised to themselves a noble monument – they have laid the foundations of a great and happy people'.9 (Even a fraction of his acknowledged idealism could yet serve us well.)

Godley was a principled as well as romantic character, and appears to have been on good terms with local Māori. It is interesting to learn of a presentation made upon his departure from an (as yet) unknown local Ngāi Tahu chief – the highly symbolic gift of a taonga pounamu (greenstone treasure).10 There is something here yet to be understood in relation to this city's foundations – related perhaps to rightful expectations and relationships. It is thought-provoking. The degree of regard in which he was held by the Canterbury colonists is also plainly manifest in Barker's August 1867 photograph of the unveiling of Godley's memorial statue, by pre-Raphaelite sculptor Thomas Woolner, in Cathedral Square. The idea of foundations laid, a city born out of one person's carefully constructed dream, remains potent even now; particularly when it may be reasonably said that many of us owe at least a part of our existence to this idea.

Alfred Charles Barker Unveiling the Godley statue, Christchurch N.Z. Aug. 6, 1867 1867. Glass negative. Canterbury Museum 1944.78.52

Did the foundations ever help support 'a great and happy people'? Were these even things we could ever become? We should return more squarely to architecture and urban design. Clearly a city's buildings and spaces are not its people, but it may be recognised that these may contribute much towards our quality of life. The American author Mark Twain saw good and pleasant things at least in the Christchurch he visited in November 1895, describing it as 'an English town, with an English-park annex, and a winding English brook [and] a settled old community, with all the serenities, the graces, the conveniences, and the comforts of the ideal home-life.'11 Looking at the visual record, it is not difficult for heritage devotees to feel that the city was at its happiest at about fifty years into the story, at around the time of Twain's visit – or perhaps later, around 1923, when Robert P. Moore brought his panoramic camera to Christchurch, Lyttelton and Sumner. Along with its satellite towns, the city has developed architecturally and carries many impressive qualities. The streetscapes are handsome and cohesive; the buildings well-crafted and sufficiently diverse, holding many details and pleasurable elements of surprise.

All this is several decades before the period in which the wrecker's ball will be given reign, making space for the profitable, 'new knows best', hulking walls and towers of modernism. (Apologies in advance to those who feel Reconstruction casts modernism as the evil baddy.) Many fine buildings will be lost; others will be retained and loved. We can also note in the early record – because we know – that some buildings look dangerous. Hindsight will be something to retain. Keeping anything much at all from our architectural past will be more difficult.

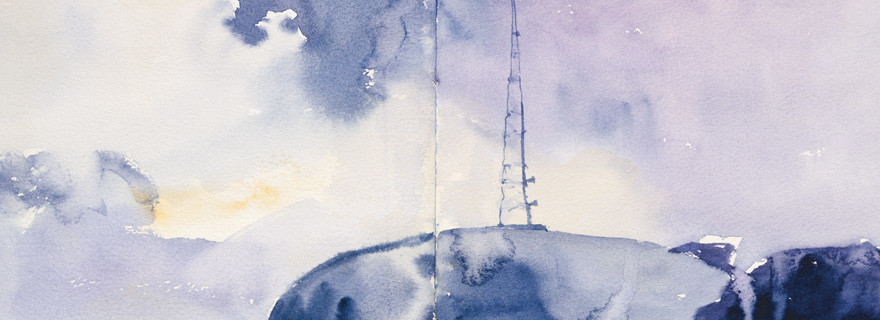

Time has been compressed in the visual record we now own. Many events – and not just recent ones – have turned artist and photographer into historian. Not all would have necessarily sought this fact. However the archival impulse attached to artistic acts of depiction and documentation has regularly been knowing and intentional. As witnesses to change, photographers such as Alfred Barker or Daniel Mundy can be seen as sharing a similar motivation to that of Murray Hedwig, Doc Ross, Tim Veling and John Collie across their unconnected years. In this study of the changing structures and spaces of our city's past, learning becomes as important as remembering. We will all bring our own histories and experience to these images. I am certain they will invite a strong response.

Tim J. Veling Support Structure, Former Municipal Chambers, Christchurch 2011. C-type digital print. Collection of the artist

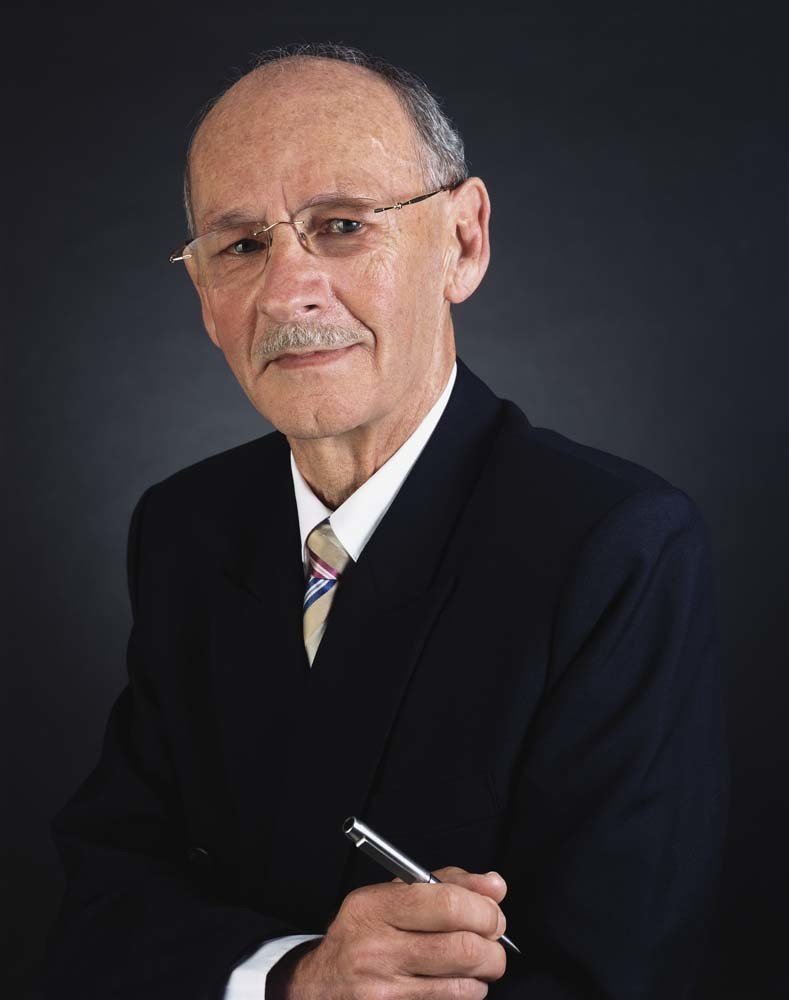

Ken Hall

Curator

NOTES

-------

1. Earlier images from within present-day Christchurch were made at the Deans brothers' Riccarton farm in 1848, by Walter Mantell (Alexander Turnbull Library, E-334-014) and William Fox (Hocken Pictorial Collections, A783).

2. The figure is evidently more than symbolic: the reverse of the drawing includes various notes, including carefully-written Māori names in another hand, one being Hoani Paratene followed by a note in Mantell's hand 'by Topi & Taiaroa. Dec. 17 Monday'. Alexander Turnbull Library, E-281-q-040.

3. See 'Black Map of Christchurch, March 1850, Sheet 3', B.M.273, Plot of Christchurch March 1850, Surveyed by Edward Jollie, Assistant Surveyor C.A., Archives New Zealand.

4. Lyttelton Times, 9 January 1858, p.4.

5. A.C. Barker, Canterbury Museum, letter transcribed by Sylvia Hall, 2002.

6. 'Earthquake at Christchurch', West Coast Times, 7 June 1869, p.3.

7. Samuel Charles Farr (1827–1918), Thomas Walter Cane (1830–1905),

William Barnett Armson (1832/3–1883), Joseph Clarkson Maddison (1850–1923), John James Collins (1855–1933), Richard Dacre Harman (1859–1927), Samuel Hurst Seager (1855–1933).

8. John Robert Godley, quoted in William Scott, The Christian Remembrancer, vol.26, London, 1853, p.320.

9. Ibid., p.322.

10. John Robert Godley Memorial Trust Collection.

11. Mark Twain, Following the Equator, 1897, p.134.

![Brian Crook: Anti-Clockwise Bride of the elevator [10:39] 2009](/media/cache/04/26/0426f04983adfe4d58c15bf0b50c47c3.jpg)

![Adam Willetts: Star Canyon 10.5.2010 [5:00 mins]](/media/cache/ce/fb/cefbe4b1f2f04e9000de04325214300c.jpg)