Robin Neate Paysage (detail) 2012. Oil on board. 250 x 200mm. Reproduced courtesy of the artist

Museums beyond museums

In this networked century, where does a museum begin and end?

Before the internet and before digitised collections, it seems that where the boundary of a museum, library or gallery lay was just understood: within its walls, curators decided what cultural artefacts were worthy of preservation and interpretation; without, the curious and the academic eagerly accepted the curators' invitation to come inside and have a look. But, perhaps due to a long institutional memory of violent sackings, museums have famously protected access to their collections with fortress-like buildings, a sharp divide between public and private space and an implied guiding principle: use equals decay.

It has pretty much always been thus. But now, for the first time, the revolutions in electronic communications afford different means of engaging with a museum collection. Every week, seemingly, brings a cheaper, better mobile device for our pockets, faster connections, and more content in digital form. Floating on this torrent are a number of interesting questions for museums and galleries. When every relevant fact, artist's biography, audio guide or hyper-detailed image from a museum's collection can be delivered to a user's pocket anywhere in the world, do visitors still need to attend in person? Even if your answer is 'Yes, of course', are there others for whom a fully digital experience may suffice? And if so, how many?

If the museum building and the physical objects it contains could be separated from all of the ideas, inspiration and conversations that those objects generate, what, then, does each side of that divide truly represent? More succinctly, does the soul of the institution lie in the stuff, or in all of the knowledge about the stuff?

Or, as one museum professional recently put it to an audience of his peers, 'What's up with the building, really?'

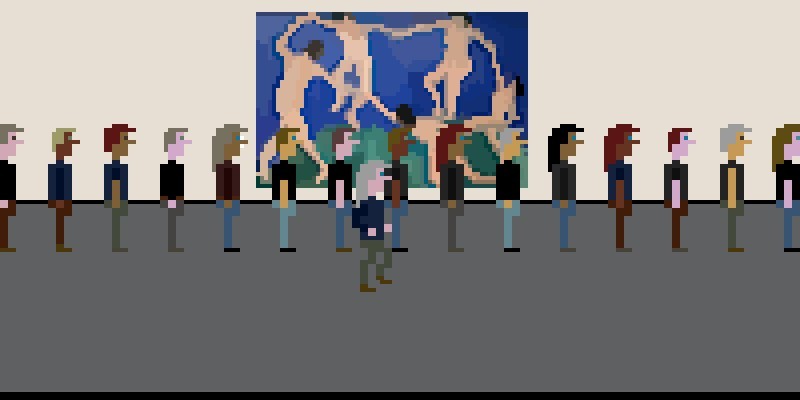

For most, the experience of visiting a great museum in person to see, hear, touch, and smell great works is not replaceable. Sensate animals that we are, we are wired to seek out physical experiences. We will always desire an audience with the Real Thing, and with one another. Even so, there are interesting changes starting to happen around, before, during and after the visit. The Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) in Hobart, Tasmania, brackets a patron's visit with online interactions: an email lets her know how to get there and what to expect, a smartphone app offers her details about the artworks during the visit (there are no physical labels in the gallery to distract), and a compendium of deeper details about her favourite artworks is delivered after the visit is over, courtesy of the app and the museum's website.

This sort of hand-holding is a smart, humane use of the available technology, and will likely be commonplace at museums worldwide in a few years' time. Outside of the lucky few with the means, geographic location and time, the typical museumgoer does not show up very frequently; often, each institution is a once-in-a-lifetime experience. But deep engagement with patrons on either side of the visit is now a welcome possibility.

Museum collections themselves have been finding new, networked expressions with a potentially global reach. From the Smithsonian Institute to the Victoria and Albert Museum to the New York Public Library, institutions are radically opening up their databases and putting everything they know about parts of their collection online. Others are successfully engaging their patrons to participate in the labour-intensive cleanup of data by transcribing a manuscript, locating where a photograph was taken on a map, or even helping to decide which works in the collection are most 'important'. Liberated by cheap digitisation, some of the rarest, most fragile treasures no longer need to be hidden; quite to the contrary, they are improved with use.

These digital artefacts can perforate the walls of the museum, enabling new views of the collections from any browser. The best of them can become collectible in their own right. With the Google Art Project, the search giant is making scans of both the interiors of major galleries and a selection of their works available on the web. The highest-resolution of these views, as a colleague of mine noted, constitute an entirely new kind of experience in and of themselves. Being able to zoom into Botticelli's Birth of Venus until every brush stroke is visible—skimming over its surface as if flying over a landscape—is an utterly novel way of seeing this most familiar of images. It is a view that would not be available to you even if you were standing in front of the painting itself. Your eyes just could not focus that precisely.

Such incredibly detailed representations will never supplant the original. But neither should we expect them to. To envision what might actually happen, consider the current state of the electronic book. For some readers, the only real books will always be those printed on paper. But for an ever-growing number of others, the convenience of carrying a hundred favourite novels in a pocket at all times is a liberating new way to read. Some books are being written that will never see print, but find an audience nonetheless. Meanwhile, great numbers of new books will still find their best expression on paper. Our relationship with museum collections is poised to undergo a similar evolution of roles.

The true revolution of digital technology's effect on culture is not that it replaces what has gone before, but that it shatters it like a supercollider, reconstituting the fragments into many different forms, some familiar and some completely new. Ideas that previously would have only lived in the printed word or the museum exhibit may now find better expression in the app, the blog, the game and the website.

Museums will continue to preserve culture and tell human stories to their patrons. Some museums will decide to remain as they are, unchanged. But other museums long to be something else, something now enabled by new technologies and networks. We should be filled with impatient wonder for what they will become, like cities after the invention of the electric light: deeply transformed by deeply complementary technologies, making them more vibrant, effective, raucous, and alive.