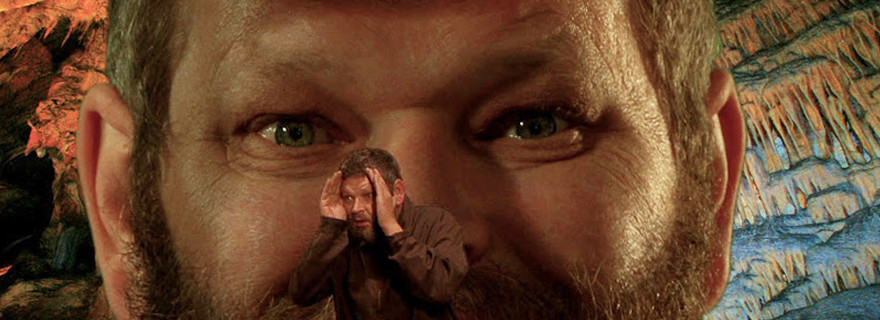

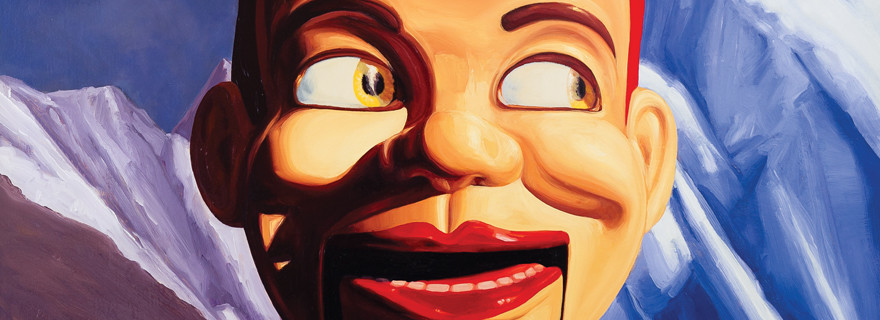

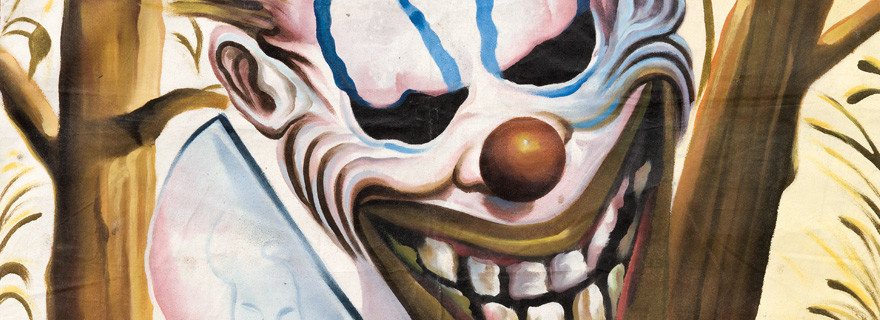

Tony Oursler Sang 2008. Fibreglass form, BluRay, BluRay player, projector. Courtesy of the artist and Jensen Sydney and Fox/Jensen Auckland

Fall tension tension wonder bright burn want

Curator Felicity Milburn on Tony Oursler and the grotesque.

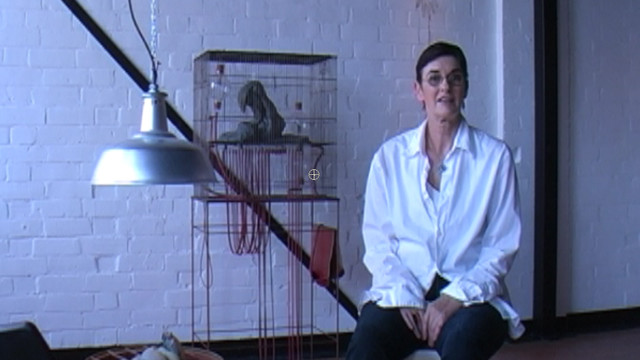

The words come slowly at first, tested out carefully like steps on spring ice, gradually building in speed and intensity. The plaintive voice stalls on certain phrases, black-stained lips repeating and worrying at them until they separate from any sense of meaning, or until a new thought breaks in. And all the while, her chameleon eyes roll, goggle, peer, blink, twitch and squint at the surrounding blackness. This is the strange, melancholy mantra of Sang, and she can't wait to meet you.

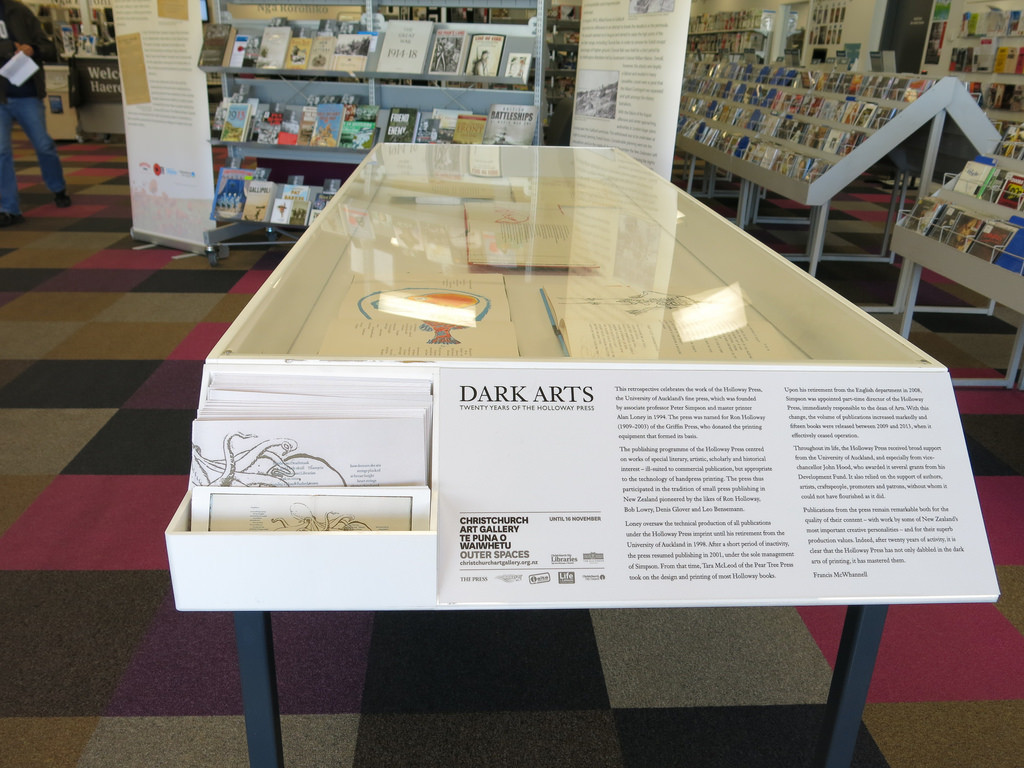

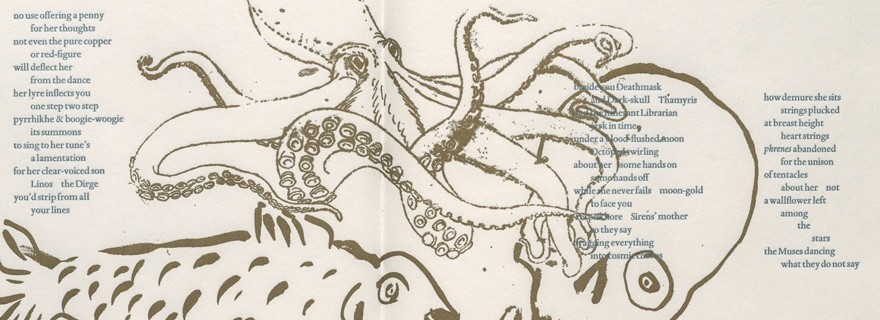

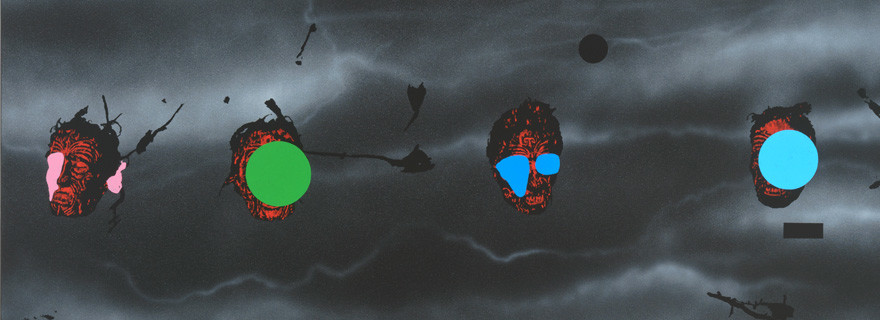

A disconcerting envoy from the parallel universe of American multimedia artist Tony Oursler, Sang embodies his trademark fusion of fractured physicality, unexpected humour and acute unease. Since the mid 1970s, Oursler has been expanding the parameters of video art, projecting his anxious, morphing images onto fibreglass forms, walls and even (in the case of his 'psycho-landscape' The Influence Machine, which was displayed on the riverbank outside London's Tate Modern earlier this year) smoke. From neurotic talking heads and multiple-personality spectacles to monstrous outdoor projections, the selection of Oursler works Christchurch Art Gallery has brought together as part of Populate! offers a fascinating take on the grotesque as a subject and style in contemporary art.

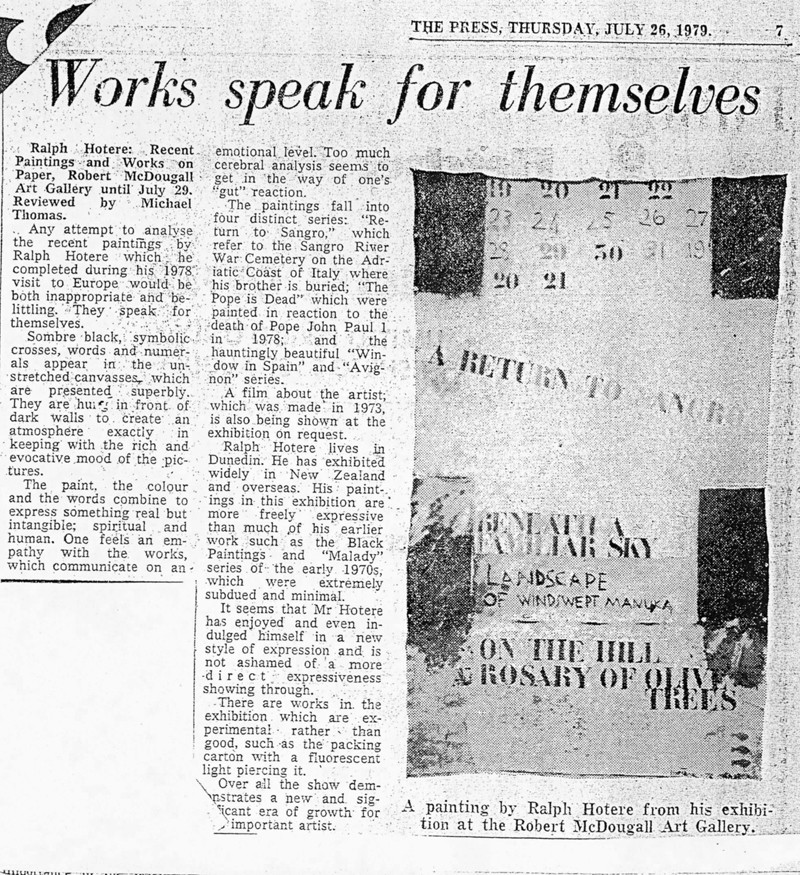

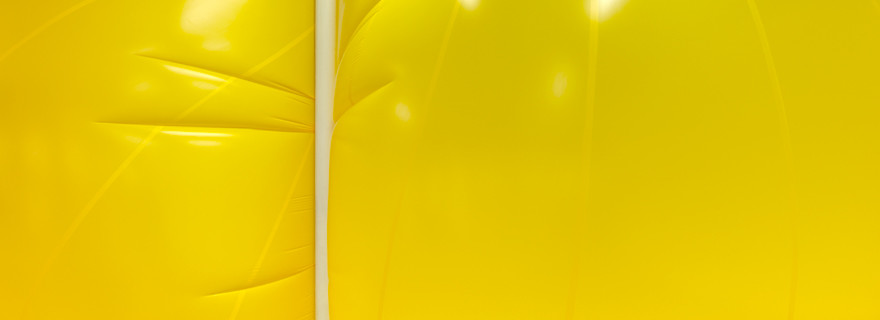

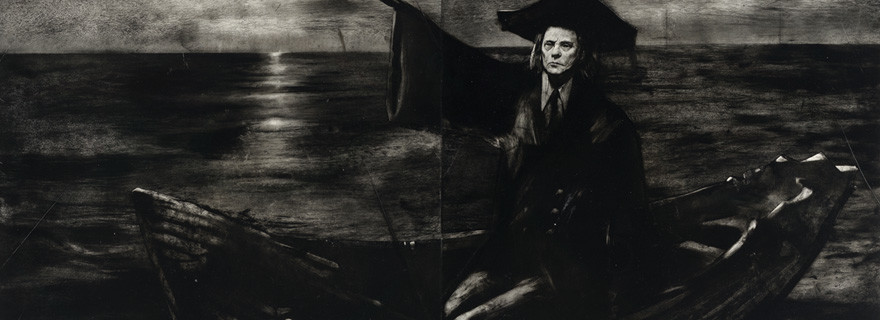

The convention of the grotesque had its beginnings in the late fifteenth century, when a series of ancient Roman wall paintings were discovered amidst the buried ruins of Nero's famed Domus Aurea. Named after the cave-like rooms in which they were found, these grottescas featured an array of fantastical, often risqué, human/animal/plant hybrids that must have presented an electrifying contrast to the serene order Renaissance scholars had previously admired in classical art. The effect of these intoxicating visions on artists and architects was immediate and profound, and their influence has been traced from the elaborate decorative designs Raphael created for the papal loggia in the Vatican, to works produced by artists in the Baroque and Romantic periods. At the end of the eighteenth century, Francisco Goya set down his own nightmarish human/animal changelings, incorporating grotesquely altered and exaggerated figures into his Los Caprichos series of aquatint prints in order to satirise the follies of Spanish society. His later, infamous, Black Paintings were visions of an earthly hell featuring witches, warlocks and a monstrous Saturn. Since the turn of the last century, the grotesque has attained a growing currency in contemporary art, prompted, perhaps, by an 'end of times' zeitgeist. Artists such as Patricia Piccinini, for example, have responded to advances in genetic modification and cloning by taking the idea of an artificially 'corrected' species to logical, but alarmingly unnatural conclusions. In 2004, Robert Storr curated Disparities and Deformations: Our Grotesque for the 5th Santa Fe biennial, with works by Louise Bourgeois, Sigmar Polke, Mike Kelley and Paul McCarthy among others (it also included Oursler's Softy, in which fragments of a distorted yellow face were projected onto a large fibreglass form, described by one commentator as resembling a giant melting marshmallow). Storr's exhibition explored the grotesque not only as a quality or subject, but as a mode of operation that places the viewer on the threshold between known and unknown, attraction and repulsion, dream and nightmare.

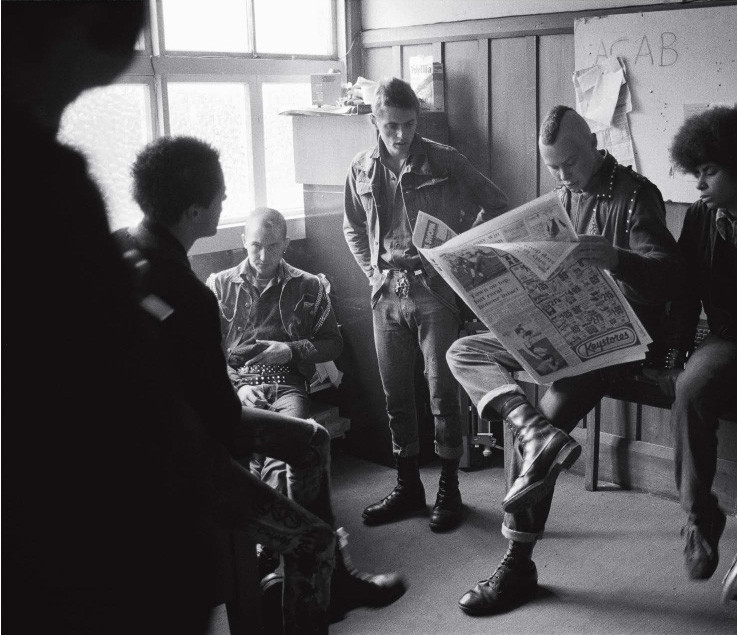

Such disruption of the familiar and expected can allow artists to open up new perspectives. New Zealand performance artist David Cross has suggested that the value of such incongruities lies in their ability to 'penetrate and unsettle the conscious self of the viewer'.1 In a 2005 installation/ performance, Bounce, at City Gallery Wellington he lay prone and almost completely encased beneath a brightly coloured inflated structure that resembled a bouncy castle for children. With only his eyes remaining visible, he was wholly subject to the attentions of visitors (friendly and otherwise) who were encouraged to take off their shoes but given no other direction. The work redrew the parameters of the conventional gallery dynamic (where the visitor looks and the work is looked at), and imbued a structure associated with innocent pleasure with the potential for inflicting injury. These shifts resulted in altered, and at times worryingly sadistic, visitor/art interactions.

Fittingly, the broad church of contemporary grotesque contains its share of darkness, as epitomised by the now-destroyed Hell (1999/2000) by Jake and Dinos Chapman, a sprawling panorama of the unrelenting horror of war played out in pitiless detail by hundreds of plastic figurines. The satirical works of Italian sculptor Maurizio Cattelan, too, often come with a nasty bite, as was the case with HIM (2001), which depicted a schoolboy kneeling in prayer, positioned with his back to the viewer. Those who came close enough to peer around the devout child discovered they were looking into the face of Adolf Hitler. In the tradition of those early Roman fresco painters, however, there's also plenty of fertile ground for those artists who prefer to temper their uneasy visions with a more playful humour.

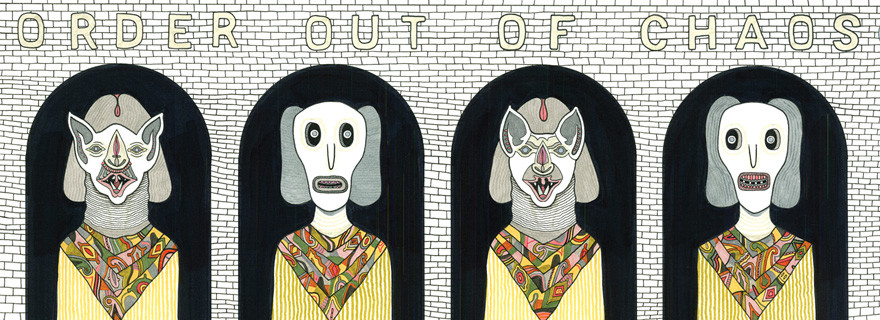

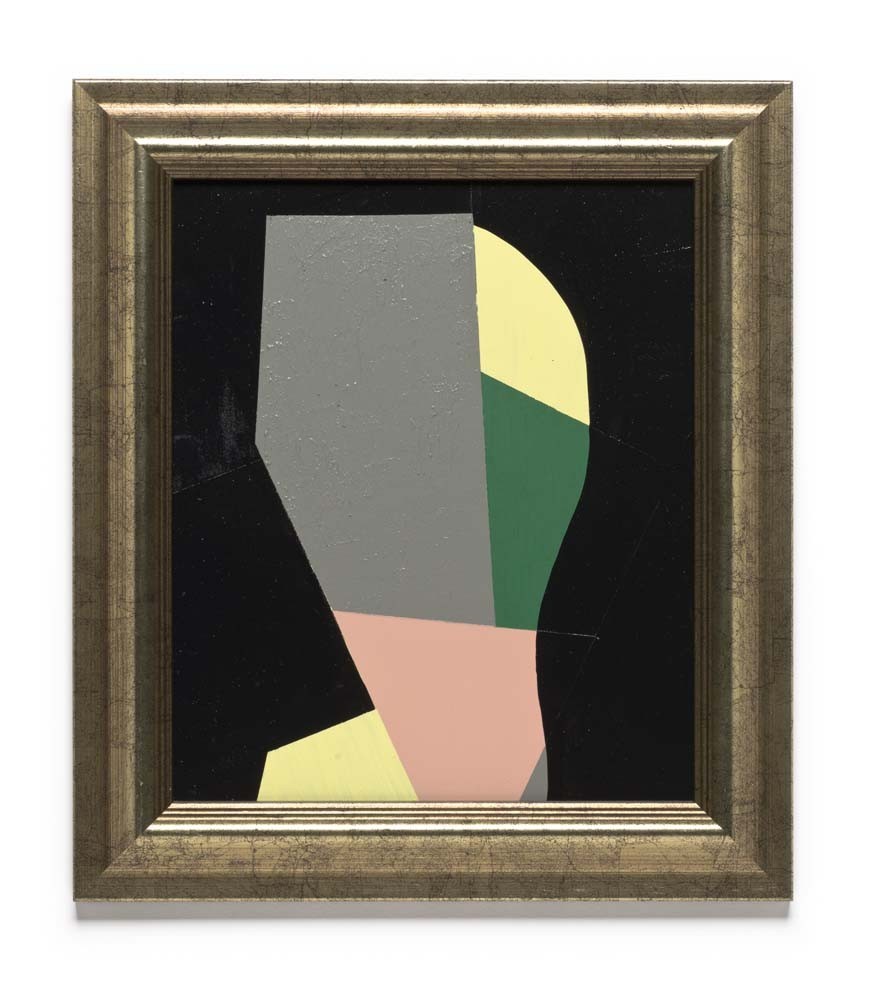

Robert McLeod Two Tongues 2002. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of the artist and Campbell Grant Galleries, 2009

For pure entertainment value, it's hard to go past the gurning, gyrating, mutating forms of Robert McLeod's electrically- coloured plywood cut-outs. Bristling with weapons, bared teeth, pop-out eyes and feral cartoon animals, Two Tongues (2001; Christchurch Art Gallery) is a chaotic and discombobulating revelation. Against elements of pure, gross-out vulgarity, the elaborate, interlaced composition projects a surprising baroque grandeur. Overriding the passivity of conventional gallery viewing, Two Tongues practically climbs off the wall to demand our attention, like a small child pulling faces, each more hideous than the next. It's a vision of life at the outer edges of the human condition, the moment after the wind has changed.

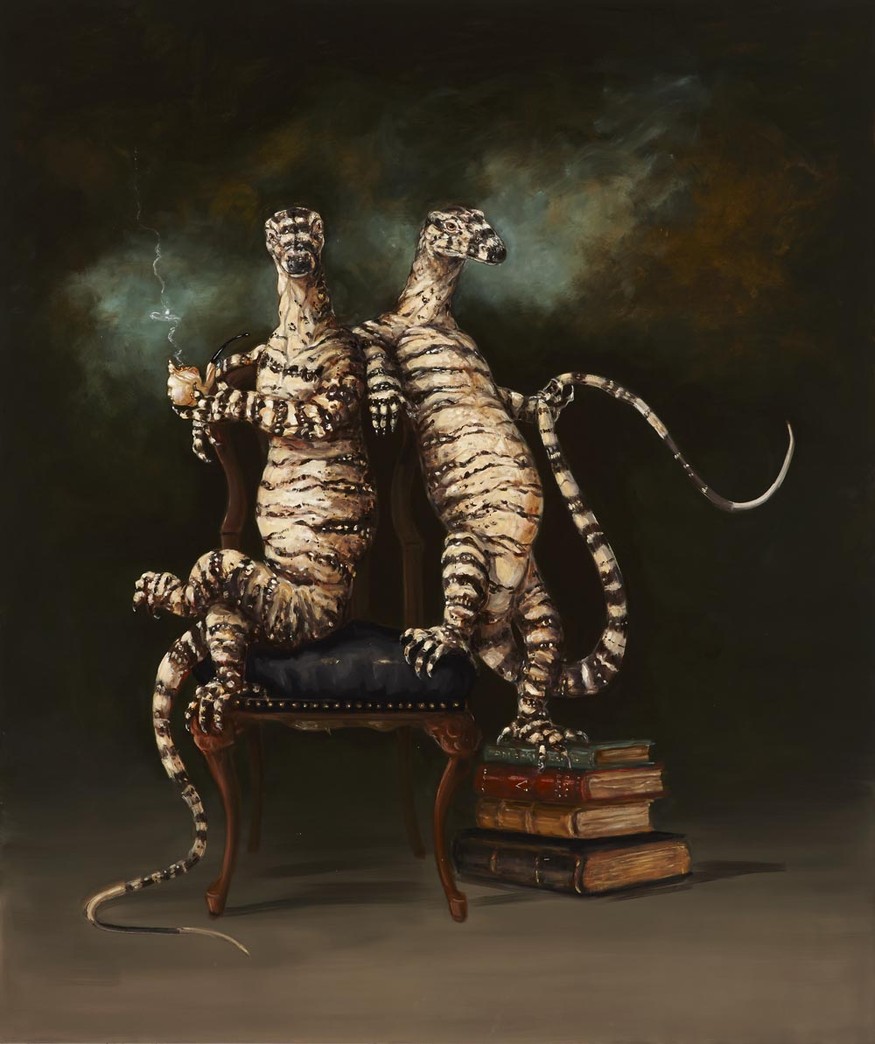

Joanna Braithwaite Lizard Lounge 2013. Reproduced courtesy of the artist and Darren Knight Gallery, Sydney. Photo: AGNSW

Upsetting any smug delusions of separation from our fellow animals, Joanna Braithwaite's deadpan reworkings of traditional society portraits combine humour with incongruous hybridity. In Lizard Lounge (2013), a pair of louche lace monitors regards us from a leather chair, their distinctly human postures and attitudes at once repugnant and charismatic. The initial, startling 'wrongness' of Braithwaite's painting is held in check by her eye for the small details that establish character; the turn of a head, the direction and intensity of a gaze, the casual grip on a banded tail or an ornate pipe. As a conceit, it's both patently absurd and highly seductive – as long as you don't think about the sound those tails would make slithering over the furniture. Braithwaite calls up a persuasive human psychology from her animal subjects, whether they be leering lizards, wayward fish or pious kereru, with a deft economy. It's a facility that is shared by Tony Oursler, whose projected personae establish themselves via the bare minimum of recognisable features – often just eyes, mouth and voice. Though their faces distort with alien tics, their failings and preoccupations are all too familiar. As monstrous as these works may be – and the theatrical Spectar (2006), with its roiling psychedelic colours and bickering multiple personalities certainly falls into that category – they are never monsters. It is the realisation of our unbreakable connection with these mutated and distorted beings – and the recognition of our own frailties and existential angst – that keeps us transfixed.

Tony Oursler Spectar 2006. Fibreglass form, BluRay, BluRay player, projector. Courtesy of the artist and Jensen Sydney and Fox/ Jensen Auckland

NOTE

-------

1. David Cross, 'Some Kind of Beautiful: The Grotesque Body in Contemporary Art', PHD thesis, 2006.

![Brian Crook: Anti-Clockwise Bride of the elevator [10:39] 2009](/media/cache/04/26/0426f04983adfe4d58c15bf0b50c47c3.jpg)

![Adam Willetts: Star Canyon 10.5.2010 [5:00 mins]](/media/cache/ce/fb/cefbe4b1f2f04e9000de04325214300c.jpg)