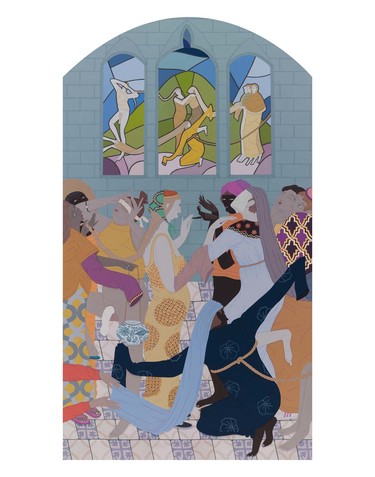

Kushana Bush The Covered Hours 2016. Gouache and pencil on paper. Private collection, Wellington

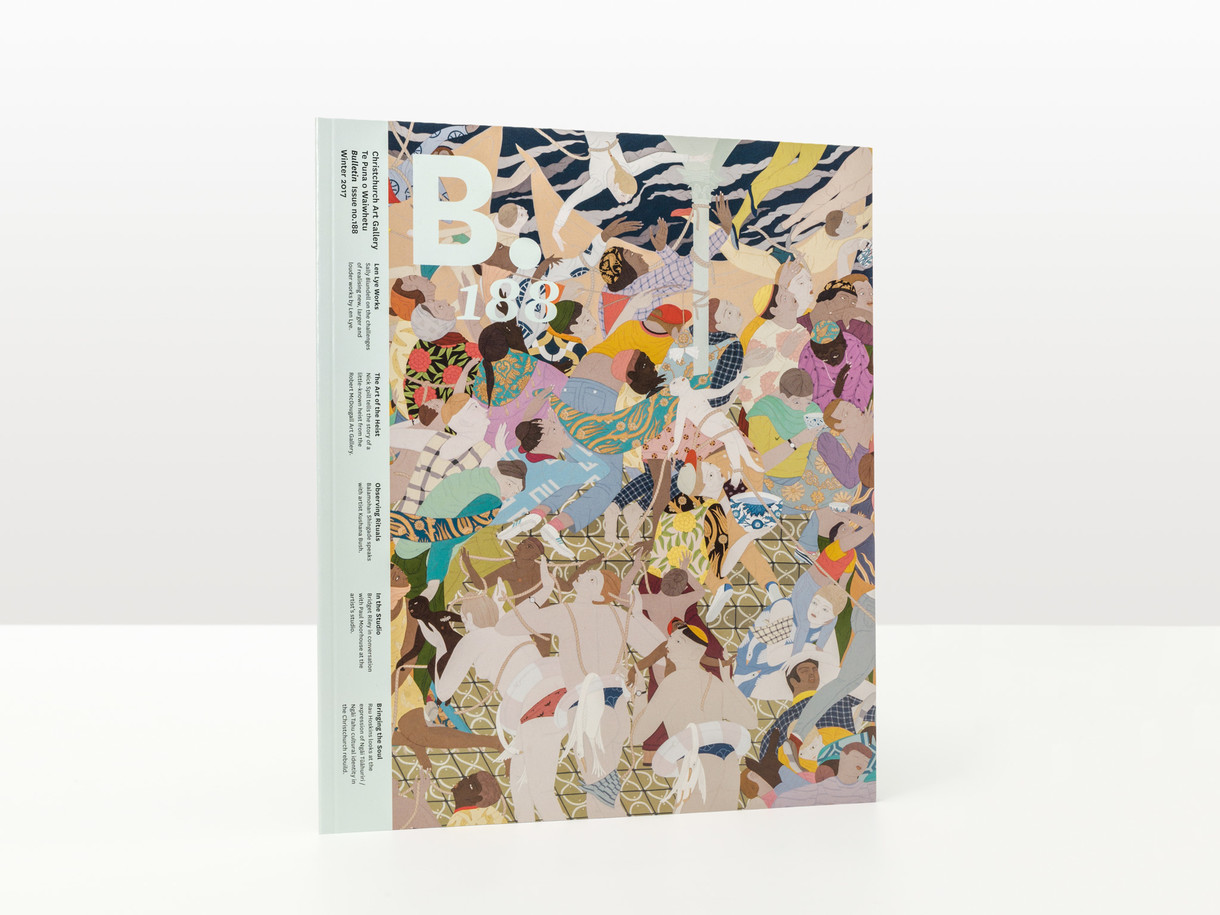

Observing Rituals

Kushana Bush is a Dunedin-based artist, whose meticulously detailed and stage-like worlds blend religious themes with secular narratives, often manifesting in ritualistic violence. Her paintings examine what spirituality, ritual and community might mean in a contemporary world. She spoke with Balamohan Shingade of ST PAUL St Gallery in February

Balamohan Shingade: There is a religious atmosphere to your artworks in The Burning Hours, and the title makes reference to books of hours – Christian prayer books found, most commonly, in the form of medieval illuminated manuscripts. Could you explain the connection?

Kushana Bush: A medieval book of hours is a lavishly illustrated collection of prayers in gouache and gold, used at hourly intervals for private devotional purposes. Illuminated manuscripts (commonly owned by women) were used the same way people fumble for their smartphones today, in a pawing kind of manner for guidance and comfort.

The finest European manuscript illuminators, to my mind, were the Limbourg Brothers. They were responsible for two exquisite books of hours: Très Riches Heures (Very Rich Hours) and the Belles Heures (Beautiful Hours). It was from this starting point that the show was titled. For me, The Burning Hours conjures up the image of a religious book burning, a concept all too relevant to our ‘us and them’ times. What acts of cultural vandalism might my artworks be subjected to over the next five hundred years?

In order to conquer these larger scale miniatures (and they really did need conquering) I was forced to adopt a kind of ascetic discipline; The Burning Hours inadvertently came to reflect those hours devoted to making. This complete detachment from socialising, Facebooking, Instagramming, smartphoning and net-flicking swims against the tide of modern life. (Is this the artist’s job? And if not, then whose is it?) This renouncing of the ‘real-world’ into my millimetre-by-millimetre world, meant that when I did have small interactions with the outside world, I really felt them. On the way to my studio, I saw a tree on fire with flowers; I watched a young boy at the pool dive into the water with a kind of hallucinatory precision. The once ignorable, became shrill and miraculous. I think this miraculous outlook is in the atmosphere of the 2016 works.

BS: It must be to achieve this more exacting, miraculous and spiritual view of the world with ‘hallucinatory precision’, that ascetics from all traditions renounce the modern world – from the sky-clad Hindu disciples of Śiva to the sufi sages of Islam, the Buddhist forest monks to the Christian desert fathers. You describe your visit to the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, in 2014 as the closest thing to a spiritual event that you have experienced. What was spiritual about it?

KB: Well I have to be honest… it was the closest thing to a spiritual experience I have had since I visited Giotto’s frescoes. To describe the Chester Beatty experience more accurately: My heart was pounding, my mouth dry; I undid my top button because I was hot and clammy; I had that urgent desire to turn away in fear of its blinding beauty… now how would you diagnose that? Would you describe that as spiritual or just great art doing its job?

The Chester Beatty Library is packed with beautifully illuminated copies of the Qur’an as well as Turkish, Persian, Mughal and European miniature paintings of the highest order. I caught myself in the act of reverently bowing down to these cabinets of miniature paintings (these private artworks can only be worshipped by one person at a time) and I felt the warm glow of gold leaf bouncing off my face like a buttercup flower held under my chin. Take that experience of awe you felt as a child at really seeing nature’s buttercup in all its fluorescence for the first time – that is what I mean by that word spiritual. A kind of transcendence, taking you out of the humdrum and into that place where the world is divine. Exquisite miniatures have this same ability to transport you.

BS: I’m reminded of being ushered through hundreds of sweaty people in the bottlenecking corridors of Indian temples. It’s an experience that’s too much for one’s senses. Life in all directions. But who are the people in your paintings, and what mysterious rituals are they engaged in?

KB: The depicted rituals include a blend of what I imagine going on outside my studio window in the streets of Dunedin and what I hear reported on the radio. A trade (or unequal sacrifice?) between two tribes, a modern-day circumcision (or some Children’s Day?), a Holy Festival/Santa Parade/Crucifixion, a twenty-first birthday party complete with a hose-pipe-beer-bong, a public immolation, a flogging, a passion play, a haruspex, a high-school hazing ritual and a no-life-lost beheading.

The who is a much harder question to answer. In all of the paintings I’m depicting the ‘you’ and ‘I’, and then in some I attempt to depict an ‘other’. I would come back to that ‘other’ weeks or months later and come to recognise some aspect of myself in them… perhaps it was a figure participating in the act of humiliating somebody else. There are parts of our humanity that a painting can make us face up to; some people find that mirror very disturbing.

Kushana Bush Flogging 2014. Gouache and pencil on paper. The Michael Buxton Collection, Melbourne

BS: This exhibition marks an extraordinary shift in the style of your paintings. Previously, seductively gross bodies floated in the middle of a page, sometimes patterned, like in Pimp Squeaks (2010), and at other times with props, as in All Things to All Men (2011). What inspired you to spill your compositions over the edge of the page?

KB: Sometimes, the biggest developments happen once you forget the all rules you made for yourself in the first place. In 2011 it dawned on me that I never let my people wear clothes – what kind of dictator had I become? I became captivated by Giotto’s use of cloth as an emotional tool, the way a firm tug or a delicate drape could signal grief or humility. I wanted to use cloth as a tool for expression, so I tentatively introduced my people to a little flannel on my return from Italy in the Tender Paintings and from then on my people shunned nudity.

My new paintings with backgrounds came about because it simply no longer made sense to carry on painting the way I had. The artwork I loved most in all my books went to the edge as a carnival of beauty contained in a rectangle. In making this technical shift I had to confront the terrifying possibility that perhaps I wouldn’t have the slightest clue on how to create a convincing setting. Because I grew up in a house of Indian miniatures and ukiyo-e, most of my art heroes are pre-perspective, so I’ve never really understood how to create the illusion of depth. I had to resort

to the primitive tricks they used to get by on, like Giotto’s hammy stage sets, Bellini’s use of a big curtain (to hide that fiddly landscape) or the way some Mughal miniaturists filled the composition up with figures (like pouring out a jug of juice until you reach the sky) thus avoiding depth altogether.

BS: Your parents named you after the Kushan Empire, because at the time of your birth, your father was involved with the local numismatic society and enjoyed learning about the old world through his own collection of Kushan coins. What’s wonderful about the legacy of the Kushan people (fl.30–375 AD) is their appetite for syncretism, their impulse to bring together various schools of thought, diverse practices and traditions into a whole. Do you share this impulse with your namesakes?

KB: What compelled the Kushans to steal their imagery from other cultures? I think it was that empty feeling of starting from scratch; they had to use what was at-hand to form something powerful and mysterious for themselves (and perhaps for those floundering around them). Who could blame them? I was born unmoored to a place, a people or a religion but moored to a magpie name. The Kushans blended Hindu, Zoroastrian, Hellenistic and Buddhist imagery to achieve something gloriously new and their own. The likeness of the Buddha image to the Greek god Apollo is all thanks to the Kushan Empire’s misadventure with art history.

This misadventure isn’t unique to the Kushans, it is the story of art history. Find me an artwork where a kind of cannibalism has taken place and I am strangely there, eager to know more. I’m very attracted to the idea of wilfully getting things wrong, it somehow cracks open more meaning.

In The Ascent of Muhammad to Heaven (or Mi’raj) the Persian artist Sultan Muhammad has hidden Muhammad’s face with a little white sheet in order to avoid idolatry. In my painting The Covered Hours (2016) figures congregate, enacting an un-pin-down-able ceremony. The extended sleeves and covered face have been borrowed here, but the original symbolic potency is stripped away. The figures now parade their once meaningful garments like some shallow fashion statement. Our modern world is filled with gestures that were once filled with meaning. Just think of the way air hostesses perform for us in the cramped aisles, summoning that tired old safety dance about what to do when we fall from the sky. I can’t help but see it as a hollowed-out death ritual.

Kushana Bush Us Lucky Observers (detail) 2016. Gouache and pencil on paper. Collection of Dunedin Public Art Gallery

BS: There was an official function and title for such clairvoyant travellers and observers of rituals in the time of the Ancient Greeks. They were called theoroi, or observers. Theoroi were sacred envoys sent by city-states to consult oracles, to give offerings at famous shrines and festivals. A city celebrating a festival would send word to other Greek city-states inviting theoroi to attend and to accept the terms of a truce covering the festival. Theoria was the word for their duties, which came to mean any act of observing, and was used by Greek philosophers, generally, to mean contemplation. And so, pilgrimage and the contemplation of rituals can be seen as the beginning of ‘theorising’. It is for this reason that I think of you as a theoroi for our times. What is the importance of ritual, do you think? Are there any similarly mysterious rituals you busy yourself with in your daily life?

KB: Fortunately for me my obsessions can be channelled rather neatly into my vocation. Rather than partakers of mysterious rituals, I think my family and I are compulsive ritual observers. My father has African dolls with human hair attached to them, where parts of their wooden body have been ritually rubbed. Collectors look for this worn patina as it means they’ve found one imbued with the magic. Some dolls are treated as if they were alive and ritualistically fed until their mouths and chins are completely worn away. In a similar, but less voodoo, vein, I have discovered smeary little marks (I think children’s fingers because of the height they reach) on the glass over the lovingly painted genitals and buttocks in my current show. I think there might be something ritualistic about this, the way people are so compelled to reach out and touch the forbidden.

BS: There is a tenderness in the way you depict the characters who busy themselves with, what looks like, a ceremonial kind of violence: the stoning of someone, the flogging of another, the potential beheadings, stranglings and immolation of people. To which god do these people offer their sacrifices? Are these characters imagined and their events fictitious or do they bear some resemblance to real world events?

KB: The facts of the world are more startling than anything my imagination could conjure up. In 2014 I saw a sixteenth-century stained-glass window from Flanders depicting St Nicholas saving three men from execution at the Burrell Collection in Glasgow; three blindfolded men lined up with hands bound in prayer as another man casually swings his sword. What strange relevance this image has to our times. This image formed the basis for my two beheading scenes, Plumes, Arrows (2015) and Us Lucky Observers (2016).

The most challenging painting I’ve completed to date was Other People (2016), which was started during the media spotlight on the refugee crisis. The image depicts a Hokusai wave of humanity surging into a flimsy cardboard blockade. The mental weight of this painting dragged me under. The turning point for the work came late, with the accidental dropping of a small figure drawing into the sky. I re-dreamed that it could be transformed into a painting with light, the sky opened up with William Blake inspired angels-turned-acrobats and I found a new exit route in the roof of the painting. All of a sudden these languishing figures were vacuum-sucked up and out of the work in the style of an ascension.

When I am debating with myself if I should really go through with creating an image that makes me as uncomfortable as Other People does, I just think of Goya.

BS: We both share a love of short stories. Do you consider your paintings stories? Would you say that you’re a storyteller?

KB: Steven Polansky’s Leg I’ve had on continual loop in my head for a year, circling around and around. I’m in the street and I think leg… that leg, how’s that leg? It’s fiction but I’ve attached so much meaning to it. It’s astounding that a storyteller can cause so much mischief with my psyche. Good storytelling, whether in art or literature, has a mysterious cycle of collapsing interpretations; it keeps you yearning and yearning.

We live in strange times. I am perched in position, ready to paint my quasi-historical accounts of this new world order.