Sideslip

An interview with Stephen Furlonger

Sydow: Tomorrow Never Knows recently opened at Gallery and the exhibition’s curator, Peter Vangioni, took the opportunity to interview UK-based sculptor Stephen Furlonger. Furlonger was a contemporary of Carl Sydow and mutual friend and fellow sculptor John Panting, both at art school in Christchurch and in London during the heady days of the mid 1960s. His path as an artist during the late 1950s and 1960s in many ways mirrored that of Sydow and Panting.

Peter Vangioni: How did you come to study sculpture at Ilam?

Stephen Furlonger: I was born in England the day after World War II was declared and my mother brought me up on her own in Dorset on the south coast until the age of thirteen, when we set sail for New Zealand – eventually fetching up at Marton in the Manawatu. When I was a pupil at the local district high school I was fortunate to have a remarkable art teacher, Bruce Rennie. It was Bruce who in 1958 recommended that I apply to Ilam, where I spent the next four years.

PV: Your tutors were artists Russell Clark and Tom Taylor – what do you remember of them?

SF: Eric John Doudney was head of sculpture and he and Clark formed the ethos of the department. They were joined by Taylor a year or so later. The emphasis was on the craft and procedures of modelling, casting, carving and, to a lesser extent, fabrication. We modelled and drew from life and drapery and Ilam’s selection of plaster casts. All of which seems extraordinarily recondite now but it was incredibly useful and worthwhile. Focusing closely on detailed study of any kind is a rare occurrence for any of us these days but it dramatised so much about oneself that seems to me to be a necessary part of making art. Things like perseverance, attention to detail and patience emerge naturally when one is dwelling closely with deceptively simple ‘descriptions’ of this order. While I can’t say that such issues formed any part of the formal teaching at Ilam they were all present and part of the general discourse, between students and between students and staff.

PV: This is where you met Sydow and Panting? Who else was studying with you?

SF: Carl and John both came to Ilam the year after I did. Although they were both from Palmerston North, which is only a few miles from Marton, I’d never met them before. Other students at the time included Alan Pearson, Tom Field, Neil Grant, Tony Fomison, Elizabeth Eames, Diana Wilson, Peter Nicholls, Matt Pine, Margaret Gorton, Claire Boocock, Anne Robson, Murray Grimsdale, Gary Baigent, Pamela North and Lyndon Smith.

PV: As a student studying in Christchurch during the 1950s and 60s what do you recall about the art scene at the time?

SF: There was precious little of an art scene as far as I can tell. The Robert McDougall Art Gallery and its permanent collection were yet to receive the ‘kiss of life’ from the appointment of professional directors including John Coley in 1980. But Coley, along with Quentin MacFarlane, was making waves in the cultural scene when I was at art school.

As far as we were concerned the ‘scene’ resided amongst recent alumni – most of whom seemed to have lived, or still lived, at 22 Armagh Street during the early 1960s. This is where the best parties were reputed to take place and where rumours of a bohemian lifestyle captured the imagination.

Practising artists like Bill Sutton, Russell Clark and Rudi Gopas also carried something of an aura and gave us some sense of the possibility, at least, of life after Ilam.

PV: In terms of international practice at this time, what was your main means of accessing the ideas of contemporary international sculptural movements here in Christchurch in 1960?

SF: The international art scene was relayed via a few contemporary art magazines and a number of dog-eared copies of Studio that lived in the library. Art International was, I think, the only regular periodical and was certainly the one most sought after. That, and the very occasional catalogues. I do remember seeing a catalogue for the 1956 Venice Biennale. Moore, Hepworth, Armitage, Chadwick, Meadows, Butler and Paolozzi were all British gods at the time, along with Giacometti, Richier, Marini, Martini and Manzù from Europe.

PV: Why did you make the decision to relocate to London?

SF: The New Zealand Arts Council had recently instituted the QEII Awards for the visual and performing arts. These allowed a lucky few to pursue post-graduate studies abroad, and I was fortunate enough to be awarded one. Three years earlier, I think, Bill Culbert and Pat Hanly had benefited in the same way and had voyaged to London – so that was a kind of precedent. At that time the cheap transport was by ship and so I set sail on the Fairsea – disembarking in Naples and hitchhiking on to London, where I arrived around June. This was too late for post graduate applications to either the Royal College of Art or the Slade. Very disappointed, I visited the Royal College to enquire about due dates for the following year and was referred to the sculpture department. I met Professor Bernard Meadows, who gave me an informal interview and said, in effect, ‘the studios are empty till the start of the new year in September. Find a corner and do some work, if we like you in September you can stay.’

Naturally enough I seized the chance and, come September, I was allowed to enrol on the four-year course. It’s not the way that things are done these days. The RCA sculpture department had an intake of about a dozen people a year and there was a strict signing in policy – as well as the requirement to inform the Professor if you proposed to get married during the course! Aside from the mandatory six-week sessions in ‘life modelling’ and the weekly life-drawing class we were pretty much left to our own devices. Meadows barked occasionally and the regular part-time staff – Ralph Brown, Bob Clatworthy, Hubert Dalwood and Bryan Kneale – struck up conversations from time to time.

The cultural studies department ran a brilliant series of lectures and confronted me for the first time with the history of ideas and with luminaries who set short courses or lectured. I recall Iris Murdoch, Hans Keller, George Steiner and Jonathan Miller – amazing!

PV: You arrived in London just as a new wave of young British sculptors were coming to the fore – compared to Christchurch this must have been incredibly stimulating.

SF: The overriding thing was the excitement and incipient competitiveness of the sculpture cohort. There was too, a sense of optimism in London in the 1960s. Roland Piché, a couple of years above us in the department, had already been taken on by the Marlborough Gallery and featured in Time magazine. David Hockney graduated in his gold lamé jacket the year that I enrolled. Pop and Op Art were spread across the newspapers and on the (black and white) TV along with the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. Ian Dury was putting together his pre-punk group and studying in the painting department… I could go on.

Linked to this was the hugely innovative revolution that had recently taken place in the UK art schools. Following a report by William Coldstream, art school education was transformed from one of individual craft-based schools (upon which Ilam and Elam were modelled) into a system in which a reduced administrative full-time staff employed practising artists on a part-time basis to generate the teaching programme and conduct tutorials. As a result there was a big increase in part-time teaching posts… and a revitalising of art education at this level.

A concomitant was, of course, an increase in the number of young artists enabled to build their practice by underwriting it with a day or two’s teaching and a consequent upsurge in the number of small commercial galleries. Without questioning it we were all carried along by the energy and euphoria that prevailed.

John and then Carl came to the UK a year after me. John followed the same path that I had; Carl spent less time at the RCA but was very involved with the ethos and certainly was deeply aware of the general excitement that prevailed.

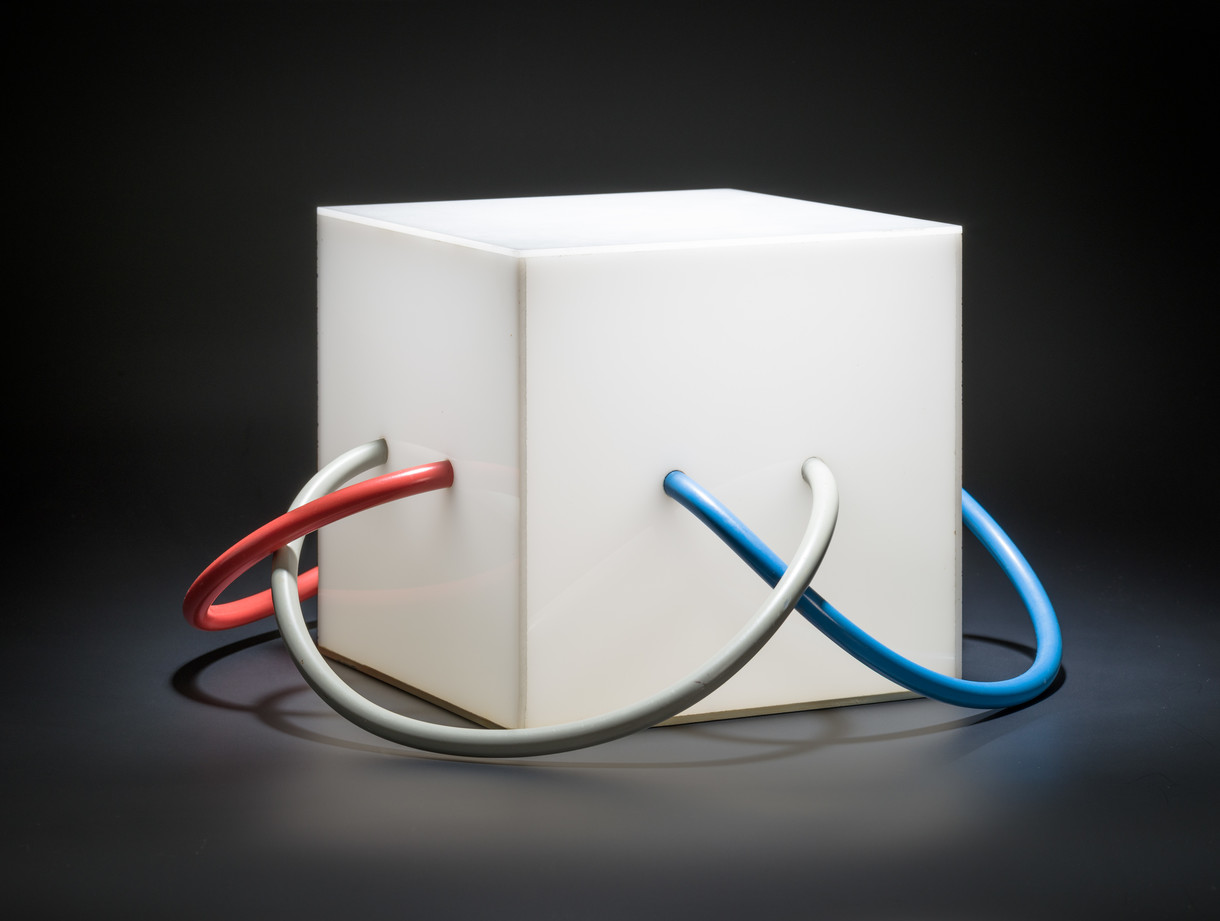

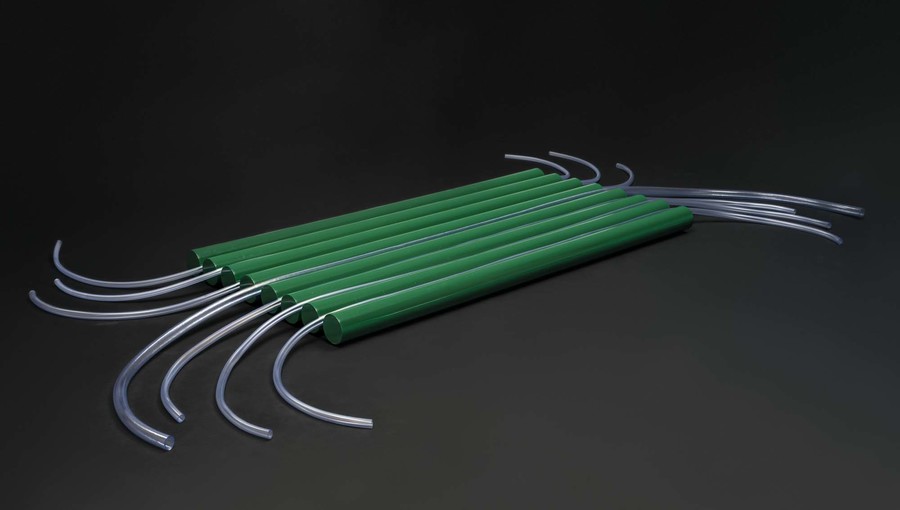

Derrick Woodham, a contemporary at the time, was picked up by the Richard Feigen Gallery in New York and took part with Piché in an exhibition curated by Bryan Robertson at the Whitechapel Gallery. It was called The New Generation and was the standout exhibition of the time. Ten or twelve young(ish) British sculptors showing brightly coloured works in the newly refurbished and perfectly white environs of the Whitechapel. Nothing on plinths and utilising a host of materials new to sculpture.

You ask about the impact that this had on me and upon John and Carl and I think there are a couple of things worth mentioning.

The first was the arrival of new materials, fibreglass in particular, upon the scene. This was unprecedented – it had no history of use and consequently none of the provenance of more traditional materials. Furthermore it smelt toxic and no one knew anything about it. John and Derrick and I were the first to engage with it and so Meadows allocated us all to the same studio and allowed us to get on with it. We muddled along making all sorts of errors but discovering along the way a means of handling it that lay outside the methods we’d all been brought up with. Put crudely, the prescribed way of making sculpture had been 1) draw incessantly 2) model in clay 3) mould in plaster 4) cast into ‘permanent’ form using plaster or cement – or, if Meadows gave the nod, bronze.

But using fibreglass we were able to generate shapes in another way. Bending and inflecting sheet-material, casting sections and building up more complex and permanent forms without the need to go through the 1 2 3-step process.

The other thing to mention at this point is that this was going hand-in-hand with an apprehension of what was happening in America at the time. Minimalism and its attendant theorising was heavily trailed in the art magazines – Art Forum and Art International – and so there was a fairly continuous debate taking place. This and the rivalry between the St Martins Advanced Course (run by Anthony Caro) and the RCA made for a vital and sometimes exciting climate.

PV: Images of the works I’ve seen by your contemporaries such as Derrick Woodham, Roland Piché, David Annesley, Michael Bolus and Philip King seem such a departure from the likes of Armitage and Moore – they’re bold, abstract and often brightly coloured, a new attitude to sculpture. Did these artists have an impact on your own work?

SF: When you’re making sculpture alongside others there is an inevitable impact – but I think that it works more as a way of locating yourself through difference rather than shared aims. I had more to do with John and Carl than anyone else and I think that this may have been a little to do with a shared background in New Zealand and particularly Ilam. Socially I saw John more often than Carl – our families were very close and we spent part of most weekends together. I also shared a workspace with John for some years so we were working together through the week as well. The main thing though was that we were all seeking to identify ourselves amid the changing world of sculpture at the time. Whilst the use of colour and gloss paint or the removal of sculpture from the plinth and the painting of bronze with emulsion all felt radical, I feel that they were the extreme gestures that accompanied us as we felt our way towards a different understanding of making sculpture.

Stephen Furlonger was interviewed by Peter Vangioni in March 2017.