Te Wheke: Pathways Across Oceania

Angela Tiatia Lick 2015. Single-channel HD video 16:9, colour, sound, duration 6 min 33 sec. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2018

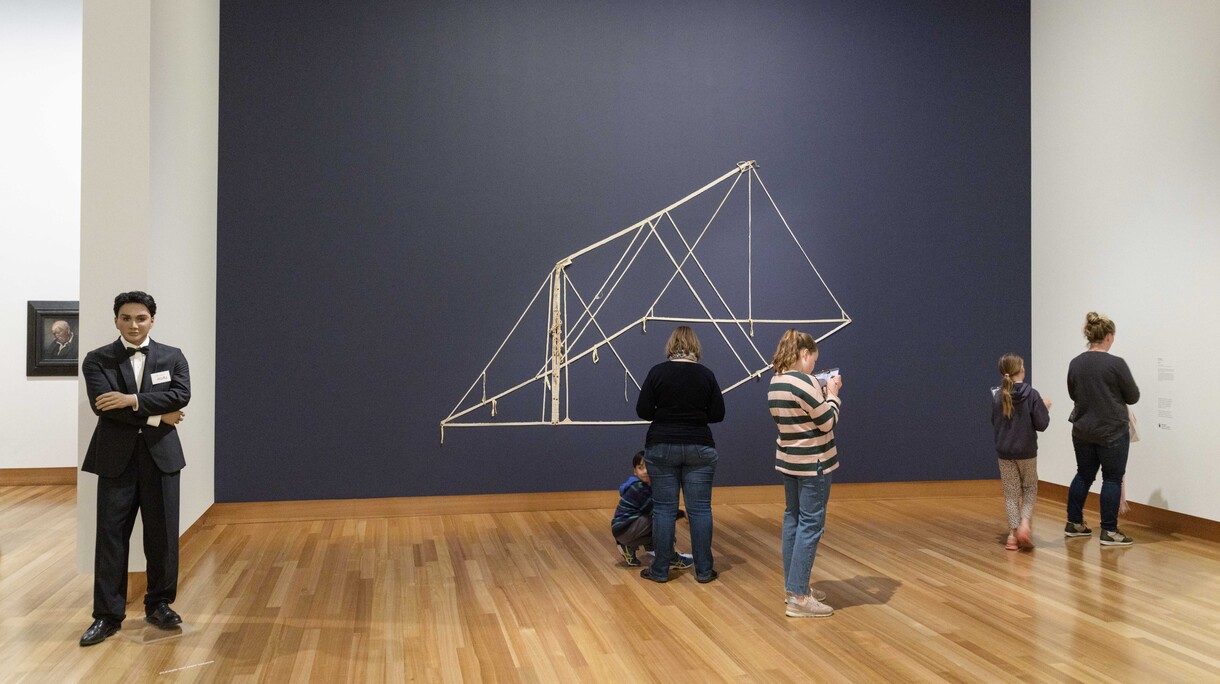

Every few years, the curatorial team at Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū embarks on a major rehang of the first-floor collection area. It’s no small undertaking finding fresh ways to combine long-held, well-known works and new acquisitions, looking for combinations that will offer compelling viewing, immersive storytelling and intellectual engagement to our wide and evolving visitor base. This time, director Blair Jackson added another dimension to our task, challenging us to reimagine the physical orientation of the spaces to encourage visitors to interact with the architecture in a completely different way.

Te Wheke: Pathways across Oceania, initiated under former head curator Lara Strongman, is our response to that brief. Instead of taking the collection’s inheritance from British and European art as its starting point, it looks from a different direction – from Oceania outwards. By exploring themes of migration and belonging, it reaches out across Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa, the Pacific Ocean, and from there to the world beyond.

Departing from our more usual linear, largely chronological approach, the physical experience of Te Wheke also spreads outward from a central point – evoking the reach of the Pacific octopus that gives the exhibition its name in te reo Māori. Symbolising exploration and connection, the adventurous, resilient wheke was sometimes used to represent the early voyages of exploration and migration Polynesian explorers made from their homelands of Hawaiki as far as Tonga, Kiribati, Hawaii, Rapa Nui (Easter Island) and Aotearoa New Zealand. This shift in perspective has allowed us to tell new stories about works that have been visitor favourites for many years, and has also prompted many spectacular new acquisitions. Te Wheke combines traditional and contemporary art forms – including tivaevae, raranga (weaving), whakairo (carving), painting, works on paper, video, sculpture, photography and installation art – with collection works complemented by key loans of taonga from significant collections around Aotearoa New Zealand.

Ken Hall, Nathan Pohio, Lara Strongman, Peter Vangioni and I were extremely fortunate to be able to work in close consultation with independent writer and curator Stephanie Oberg on all aspects of Te Wheke, from the exhibition and related publication to the public programmes that will accompany it. Her links within the Cook Islands community and the insights and wider perspective she offered us throughout the project were integral to its development and offered us many opportunities to expand and enrich our thinking. We hope that the exhibition will surprise and delight our visitors, and that it will open up many conversations about the tensions and connections that continue to shape our past, present and future in Aotearoa.

For this Bulletin, four of the Te Wheke curators have chosen a single work from the exhibition to explore in greater depth.

Felicity Milburn

Lead curator

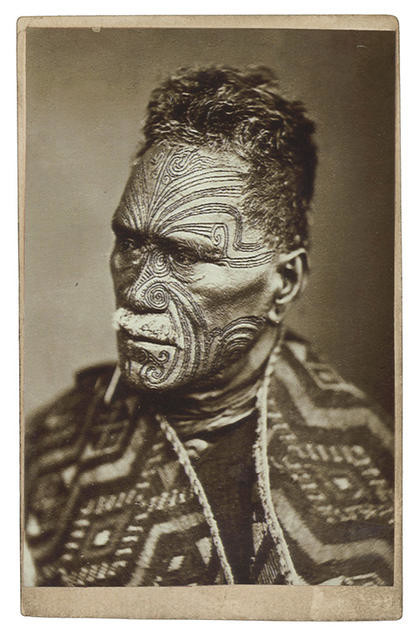

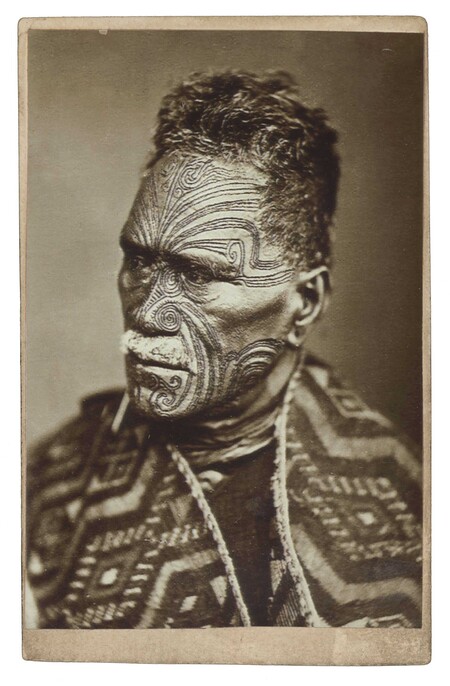

George Albert Steel (photographer), Elizabeth Pulman (publisher) King Tāwhiao Tukaroto Matutaera Pōtatau Te Wherowhero (Ngāti Mahuta, Tainui) 1882. Albumen carte de visite. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2019

Tāwhiao Tukaroto Matutaera Pōtatau Te Wherowhero, the second Māori King, had his photographic portrait taken many times in New Zealand, as well as during well-publicised 1884 visits to Australia and England.1 The story behind this portrait shows that King Tāwhiao sometimes commissioned portraits, and collected portraits of other leading chiefs. As a celebrity sitter, he was also aware that his likeness represented a prized potential income for the studios he patronised.

This photograph was taken in Auckland in January 1882, following Tāwhiao’s famed re-emergence into the public realm. Seven months earlier, he and his followers had declared the peace that ended his eighteen years of isolated rule in Te Rohe Pōtae, ‘the King Country’; an attempted resistance by Waikato-Tainui to colonisation. On 19 January 1882, the King and his entourage were welcomed into Auckland with a grand civic reception, banquet and conducted tour of attractions. Their afternoon commenced with a visit to Elizabeth Pulman’s Photographic Rooms in Shortland Street to view her collection of portraits: “accompanied by a number of native chiefs, and Major [Gilbert] Mair and Major Jackson”, Tāwhiao “visited Pulman’s photographic gallery, and spent some time inspecting the photographs of Maori chiefs, of which it contains a great variety.”2

Back in Auckland after five days with Mair on the North Shore, Tāwhiao was taken with his three sons and other Kingite leaders to Robert Bartlett’s photographic studio for a portraiture session. They also revisited “Pulman’s photographic gallery, where Tawhiao inspected a large number of photographs of native chiefs, and selected some. He also intimated his intention of sitting there for his portrait on his return from Kaipara. This concluded the day’s sightseeing.” Returning to Auckland on 28 January “[t]hey visited a number of places of business, among others Pulman’s photographic gallery, where Tawhiao and some of the leading chiefs sat for their portraits, and some excellent likenesses were obtained.”3

Elizabeth Pulman (née Chadd) and her husband George, a mapmaker and lithographer, had emigrated from England in 1861. Their business involvement with photography evidently started in 1863 when George became agent for Thomas Armstrong Fairs and George Albert Steel, who (after arriving together from London in July) purchased James Davis and Alfred Rayner’s negatives, then (from October) sold prints and advertised their services through “Mr Pulman’s Draughtsman, Shortland-street.” George Pulman ran his own photographic studio, likely with Elizabeth’s assistance, from 1867 until his death on 17 April 1871. Elizabeth took over the studio and was first referred to as a photographer herself in an advertisement in September. Having two step-children and five younger children to raise, she employed Steel as her principal photographer from 1874 at the latest. 4 In September 1882, George Steel testified in court to having taken this portrait of Tāwhiao, after another Auckland studio copied and sold it as its own.

Regularly published appreciation of Steel’s work for Elizabeth Pulman included an account from 1885, when “King Tawhiao and a number of his party paid a visit to Pulman’s photographic establishment… and, Tawhiao especially, expressed admiration of the new series of Hot Lake views, taken… by Messrs Steel and [Frederick] Pulman.”5 Steel was certainly responsible for many of the striking photographs usually solely credited to his better-known employer.

Ken Hall

Curator

Cath Brown Kiwi Kete 1990s. Harakeke, kiwi feathers. Collection of Elizabeth Brown, Christchurch

Cath Elizabeth Brown was a tohunga raranga, a master weaver of national and international reputation, a specialist educator in the arts, and present at the first phase of what became known as contemporary Māori art. Brown wore many hats, from her marae at Taumutu and organisations with local, national and international reach. She worked across various media, but it might be fair to say her heart was enamoured with mahi raranga / weaving.

Born to a Māori father, Arnold (Arnie) Henry Brown, and a Pākehā mother, Winifred (Winnie), Cath was often found among the harakeke plants near her parents’ house at Taumutu on the southern shore of Te Waihora Lake Ellesmere. It was through her mother that Brown was introduced to “the first simple movements of weaving”. 6

Brown finished her schooling at Christchurch Girls’ and enrolled at Dunedin Teachers College, and in 1953 she was selected by the artist Gordon Tovey to become an art and craft teacher and advisor for the Education Department. Tovey had studied at the College of Creative Arts in Wellington in 1921, and he and fellow student Len Lye shared a deep belief in art as an intuitive, wide-reaching and inclusive practice that transcended notions of culture, genre and fashion. Tovey brought Brown into an experimental program he had been developing for some years. She was the only Ngāi Tahu member to attend the first Tovey workshops held at Ruatoria in March 1960, a historically significant education programme known as the Northern Māori Project, led by master carver Pine Taiapa. The programme aligned with Māori interests in keeping traditional Māori art alive, seeing the teaching of art enter the public school system while also supporting the new-formed frond of Māori contemporary art practices. The programme resulted in the formation of Ngā Puna Waihanga, the first Māori organisation for artists and writers. Brown led the Waitaha Tai Poutini branch of the organisation. With tenderness and determination she encouraged the arts of raranga through educational institutions and other roles she occupied in Te Waipounamu.

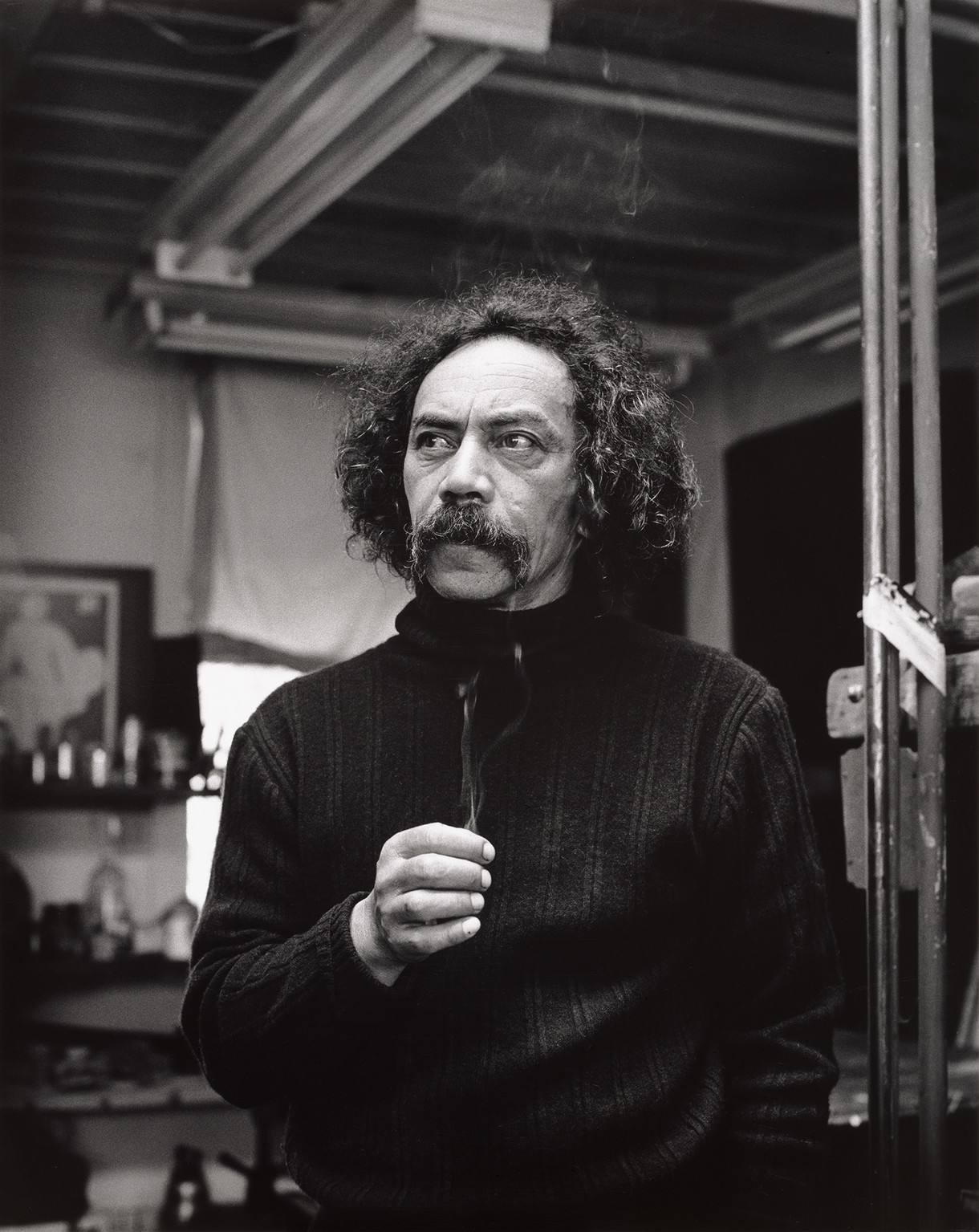

Other artists on the program included Elizabeth Ellis (née Mountain), Fred Graham, Ralph Hotere, Freda Rankin Kawharu, Mere Kururangi, Mere Lodge (née Harrison), Katarina Matiaia, Sewlyn Muru, Marilynn Webb and Arnold Manaaki Wilson. Brown was ambitious and driven, as her resume contests, and was certainly recognised and respected alongside her wāhine toi colleagues from within the Māori Modernist Movement and the generations of younger artists to whom she offered insight, encouragement and support. Brown’s daughter Elizabeth says:

Cath had to carve out a space in an often male dominated art world, which reinforced the strong determination for both herself and other artists to be visible and recognised. This then was the basis for her passion to inspire, support, encourage and nurture upcoming young artists, she did not limit this to just artists. There are many people who recognise the positive impact she had on their lives.

Cath was quietly proud of [Kiwi Kete] and it became part of a number of exhibitions, often accompanied by a smaller kete holding muka and feathers. The Kiwi Kete is one of the more traditional pieces that Cath made... an exquisite piece of workwomanship, it epitomises the skillset that Cath had. It is delicate and beautiful in its form. 7

Elizabeth Brown has allowed this taonga to reside as a long-term loan in the care of Te Puna o Waiwhetū Christchurch Art Gallery.

Nathan Pohio

Curator

Angela Tiatia Lick 2015. Single-channel HD video 16:9, colour, sound, duration 6 min 33 sec. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2018

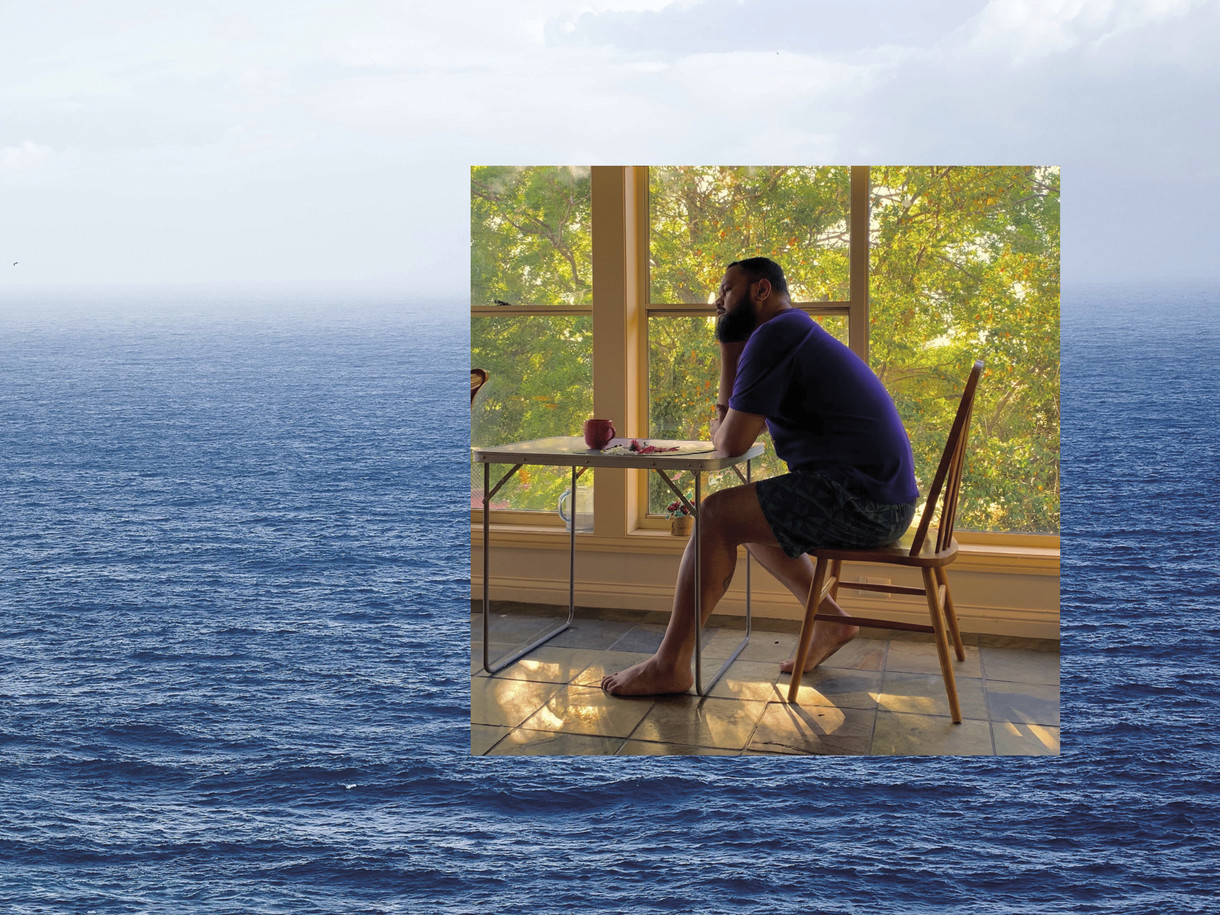

One of the challenges of climate change is that to many people – the lucky ones – it can feel almost as abstract as it is overwhelming. We read the reports, we acknowledge the effects, but we don’t register its urgency on a personal level. That’s not a luxury afforded to everyone, of course, including many of our Pacific neighbours. Filmed in the waters off Tuvalu, one of the nations most endangered by rising sea levels, Angela Tiatia’s video work Lick brings the impact of global warming up close and personal. The average height of the islands is less than two metres above sea level, and the higher saltwater table is already threatening staple deep-rooted food crops like coconut and taro. Eventually, the Tuvaluan people will be forced from their homes.

Seen from the side, from underneath the waves, a woman stands strongly on a flat stone of white coral, facing off against the waves as the high tide washes in. Her hands touch the surface of the water, sometimes reaching through it towards us, but her head remains out of view. As the tide rises, she struggles to keep her balance until finally she’s ‘licked’ by the water: a wave lifts her off her feet, she falls backwards and slowly floats away.

As in most of Tiatia’s works, the body featured in Lick is her own. After growing up within a Mormon household in Auckland, and then working as a model during her teens, she developed a keen awareness of how women’s bodies are policed and constrained. It left her determined to take control of her own representation, and inserting herself into her works became a way of closing down the variables, allowing her to explore female strength and sensuality without exploitation. In Lick, Tiatia’s malu, a traditional leg tattoo and adornment specific to Samoan women, can be glimpsed in flashes through the shifting water. By revealing it, Tiatia is breaking a subtle cultural taboo, but also adding a layer of symbolism to her act of endurance, since the malu is traditionally associated with cultural responsibilities, sheltering and protection.

Lick is a desperate balancing act, an unforgettable embodiment of the vulnerability imposed on Tuvalu, and other nations around the Pacific, through the action, and inaction, of others. But against the dominant gurgle and hiss of the ocean is another, smaller sound. As the small piece of coral Tiatia is standing on moves it grates gently against the ocean floor. It’s the noise of one small object pushing persistently against a much larger one. It’s the sound of resistance.

Felicity Milburn

Lead curator

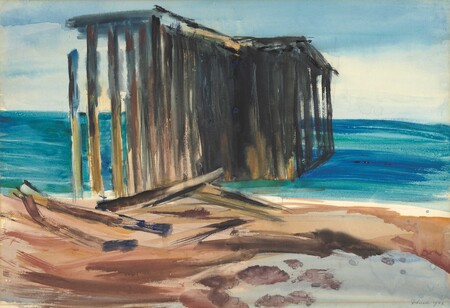

Doris Lusk Acropolis, Onekaka (The Wharf) 1966. Watercolour. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, Lawrence Baigent / Robert Erwin bequest, 2003

“It just interested me as an image, the beautiful beach and the wharf and the cross-currents of the sea … the whole beach was so beautiful.” 8

Many of us have that special place in the world we feel a strong connection to, that spot we return to regularly to relax and recharge. For the painter Doris Lusk it was the beach at Onekaka in Golden Bay. Lusk first visited Onekaka in 1965 and was immediately struck by the remnants of the old wharf that led out into the bay. This wharf was to become an important subject in her work and she was drawn back to the region regularly over the following years, exploring the motif of the broken wharf in larger oil paintings made from her watercolour studies.

The drive to Takaka from Lusk’s hometown of Christchurch is epic and includes the final daunting climb over Takaka Hill, with no less than 300 bends in the road, before you drop down into the peaceful valleys of Golden Bay below. Onekaka is, like much of Golden Bay, an area of outstanding beauty. Standing on the beach you look out over the serene waters of the bay, and turning round to face inland the densely forested hills rise up into the Kahurangi National Park with Parapara Peak dominating. In amongst all this natural beauty Lusk became captivated with the forms of the dilapidated wharf, which was built in the 1920s to ship iron ore from a local mine. Like much of her work, she focuses on human intervention within the landscape, the industrial set amongst the natural. Here she draws parallels between the remnants of the humble wharf at Onekaka and the ruins of the Acropolis, the wharf’s piles mirroring the Doric columns of the famous ruins in Athens.

It’s no coincidence that there are three paintings depicting the beach at Onekaka amongst the collection of art bequeathed to the Gallery in 2003 by Lusk’s friends and supporters Lawrence Baigent and Robert Erwin. As well as two paintings by Lusk there is an example by Leo Bensemann, another artist who had very strong connections to this region. Golden Bay and the beach at Onekaka was a region that they all travelled to regularly to enjoy their summer break from Christchurch.

Sitting on the beach at Onekaka today the piles, once seemingly so solidly stoic, have been reduced to mere stumps, marching out into the bay at low tide. Onekaka remained significant to the end for Lusk; on her last visit, just months before she died in 1990, she began a self-portrait of herself at Onekaka that unfortunately remained unfinished.

Wharf at Onekaka

Feathers of darkness twitch a sea

Not yet broken. Darker looms

The massed sky descending over

Last gouts of light. Black into storm

Stumbles the broken cortege of piers.9

Peter Vangioni

Curator